Here, taken from the ECF Facebook page, is US chess legend James Sherwin (92) taking on English prodigy Bodhana Sivanandan (10) in the recent UK Open Blitz Qualifier in Cardiff. Two players with an 82 year difference in their ages.

Back in the 1970s it was a regular trope every year at Hastings and the British Championship for the press to feature a photograph of the oldest and youngest competitors sitting opposite each other. It’s debatable whether this sends a positive message that chess is for all ages or a negative (and totally false) message that chess so simple that it is only for the very young and the senile.

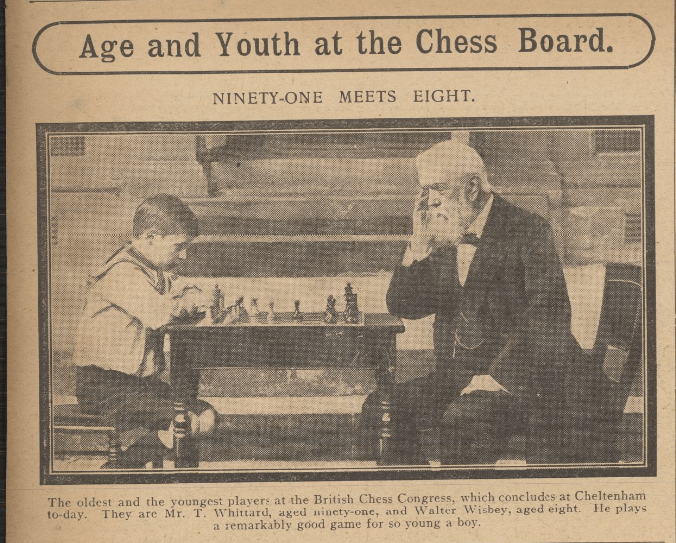

Here’s a much earlier example: a photograph taken at the 1913 British Championships in Cheltenham.

This time we have an 83 year gap in the ages of the antagonists. Of course I wanted to find out more about both players.

Our venerable greybeard is Thomas Whittard (9 September 1822 – 1 April 1919) and our sailor-suited boy is Walter Henry Rhodes Wisbey, who also lived a long life (3 April 1905 – 1993). Whittard was born in the same year as Edinburgh Chess Club, 12 years before what might be considered the first modern international chess competition: the series of matches between La Bourdonnais and McDonnell. Wisbey died in the year of the Kasparov – Short world championship match, when computers were approaching GM standard. A photograph which straddles over 170 years of chess history.

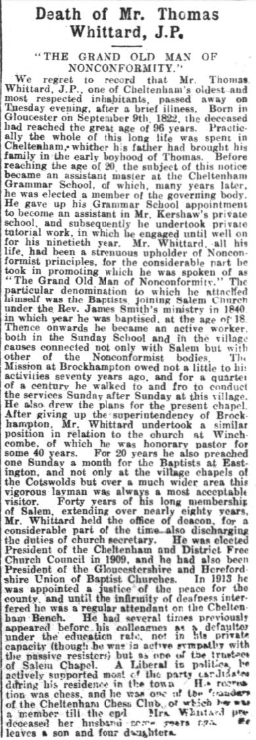

Whittard was born in nearby Gloucester, one of a large family which moved to Cheltenham when he was a young boy. He would live there all his life, a much respected member of the local community.

He started off as a schoolmaster, soon becoming a private tutor in classics and maths, giving him more time for his other calling: spreading the word of God. Thomas Whittard was, all his life, a leading member of the Non-Conformist movement in his home town.

His main recreation was chess, which he probably learnt as a boy or a young man. I presume he was the T Whittard who required clarification of the en passant rule from Staunton in the Illustrated London News in 1845.

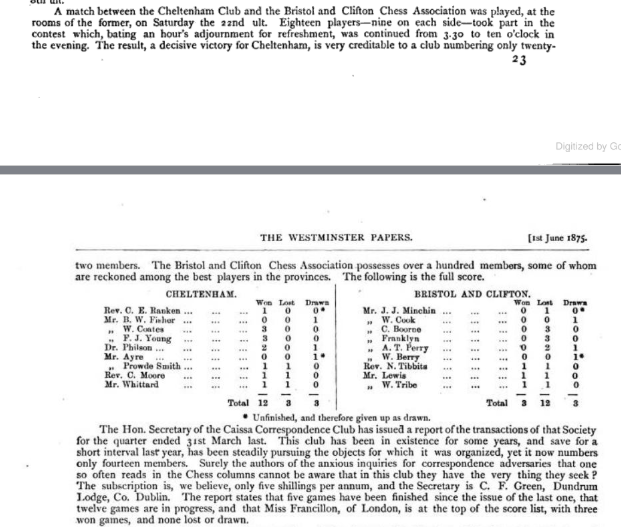

The first Cheltenham Chess Club was briefly very active between 1874 and 1876, though it had probably been formed a few years earlier, and gradually wound down a few years later, its prime mover, William Coates, a Yorkshire born schoolmaster, chess player and problemist, having left the area.

This match report indicates how successful the club was.

You’ll see that they included two genuine master players, Charles Ranken, one of the ‘fighting reverends’ and Bernard Fisher, among their number, both of whom had made the 25 mile journey from Great Malvern to take part. Thomas Whittard just made the team on bottom board.

I was also intrigued by Miss Francillon of London in the following news item: if she’s who I think she is she also had strong Cheltenham connections.

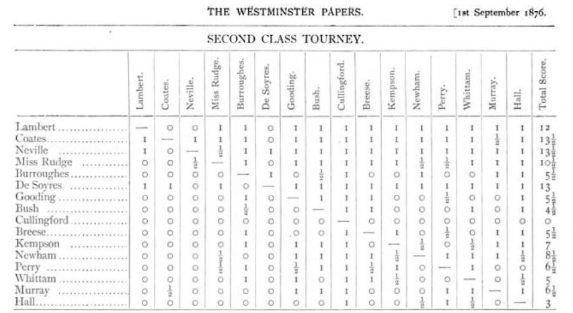

The following year, Cheltenham hosted the annual meeting of the Counties Chess Association. Fisher and Ranken both played in the top section, which was won in convincing fashion by Amos Burn.

Coates shared first place in the Second Class section, with Mary Rudge performing strongly, and Thomas Whittard (misnamed here as Whittam) managing a few points.

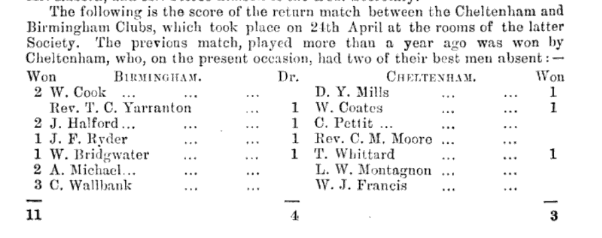

Here, from the Chess Player’s Chronicle (June 1880), is a match featuring Whittard on Board 5.

At this point Coates was still around, and another strong player, Daniel Mills, had been recruited.

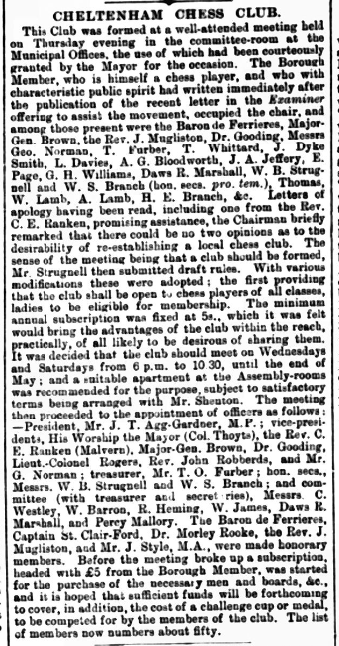

This club gradually died away, but in 1889 the good people of Cheltenham decided it was time to start a new club.

The leading light behind this club, which is still active today, was William Shelley Branch, player, problemist, organiser, journalist and historian, who really deserves his own Minor Piece. You’ll see that Thomas Whittard, now in his late 60s, was also involved, one of the few survivors from the earlier club.

We have a correspondence game from this period, against Herbert Dobell of Hastings, who was punished for a couple of tactical oversights.

[Event “Correspondence”]

[Date “1892.??.??”]

[White “Dobell, Herbert Edward”]

[Black “Whittard, Thomas”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bg5 Be7 5. e5 Nfd7 6. Bxe7 Qxe7 7. Qd2 a6 8. Nd1 c5 9. c3 Nc6 10. f4 cxd4 11. cxd4 Qb4 12. Qxb4 Nxb4 13. Ne3 f5 14. Nf3 Nb6 15. a3 Nc6 16. Be2 Bd7 17. O-O Rc8 18. Rac1 O-O 19. Rfd1 Na8 20. Rc3 Nc7 21. Rdc1 Na8 22. Rb3 Nxd4 23. Rxc8 Nxb3 24. Rc3 Na5 25. b4 Nc6 26. b5 axb5 27. Bxb5 Nxe5 28. Nxe5 Bxb5 29. Rc5 Ba4 30. Ra5 Nb6 31. Rc5 Rc8 32. Nd3 Kf7 33. Ne5+ Kf6 34. Ra5 d4 35. Nf1 Rc2 36. Ra7 Bc6 0-1

Throughout the 1890s and 1900s Whittard took part with the enthusiasm of someone a third his age in matches against other towns and cities as his town chess club continued to thrive under the patronage of local MP and latter-day gay icon James Agg-Gardner.

A highlight was the visit of World Champion Emanuel Lasker to give a simul in 1898, while there were also more light-hearted events such as matches between smokers and non-smokers in 1906 and 1907: such novelty matches were popular at the time as season openers: Whittard was, quite rightly, a non-smoker.

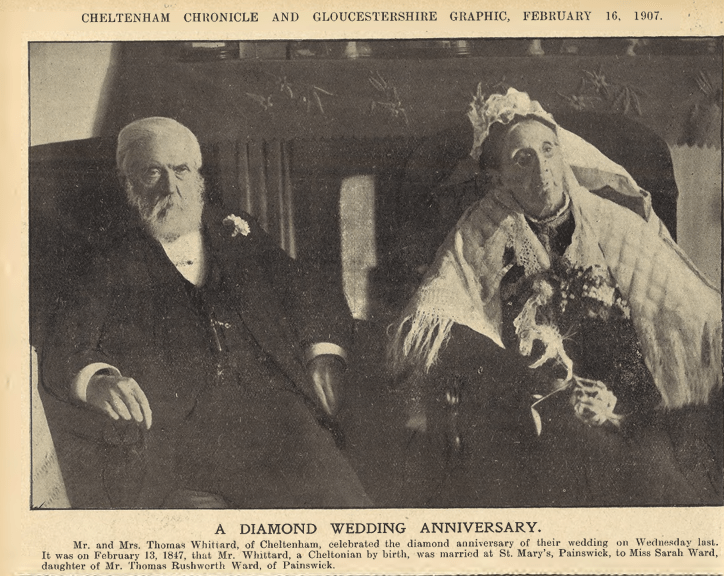

1907 was a momentous year for Thomas Whittard: he and his wife Sarah celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary. Thomas and Sarah, who died a year later, had eight children, three sons and five daughters. Four of their daughters never married, continuing the family tradition of teaching and preaching instead. You can read about three of them here (pages 16-17)

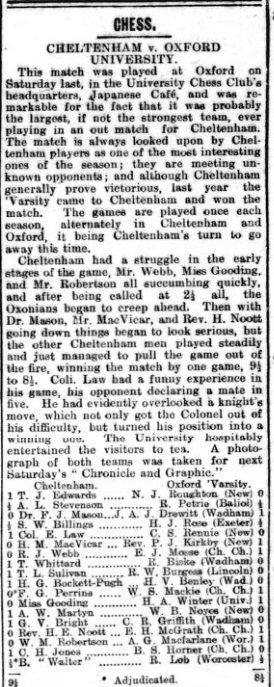

Here’s a 1908 match against Oxford University, where Whittard won his game on Board 8. You’ll notice the mysterious “Walter” on bottom board, as well as AW Martyn, whom we’ll meet later and the eccentric Miss Annie Mabel Gooding, who deserves her own Minor Piece.

In 1912 it was suggested that Cheltenham should host the following year’s British Championships, and Whittard was elected to the committee formed to discuss this.

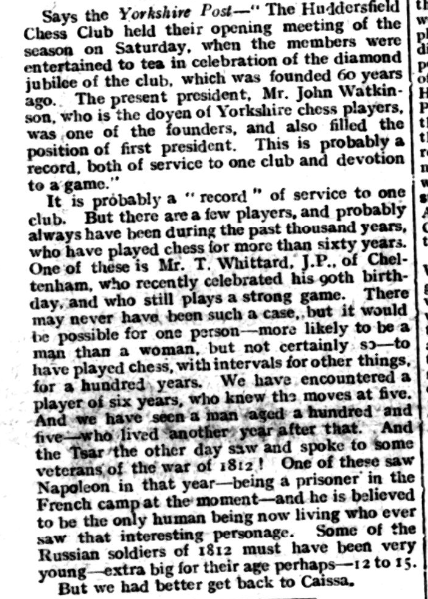

He was appointed a magistrate in his 90th year (a pretty remarkable achievement) as you can see from the ‘J.P.’ after his name in this tribute.

The following August the British Championship took place as planned. You can read an excellent and detailed report on BritBase here.

Due to a late withdrawal, Thomas Whittard was persuaded to play in the Third Class A section, only his second public tournament. He won his first four games, but eventually finished on a 50% score.

Here’s his first round victory against William Marcus Brown, a blind music teacher from Liverpool.

[Event “BCF-ch 10th Third Class A Cheltenham R1”]

[Date “1913.08.11”]

[White “Brown, William Marcus”]

[Black “Whittard, Thomas”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 exd4 4. Nxd4 Be7 5. Bc4 Bf6 6. Nc3 c6 7. O-O Ne7 8. Re1 O-O 9. Be3 Ng6 10. f4 Be7 11. Qh5 Bd7 12. Rad1 a6 13. a4 c5 14. Nf3 Qe8 15. Nd5 Bd8 16. Ng5 Bxg5 17. Qxg5 Qd8 18. Qxd8 Rxd8 19. Nc7 Ra7 20. Rxd6 Rc8 21. Nd5 Bxa4 22. Nb6 Re8 23. Nxa4 b5 24. Bxc5 Rc7 25. Red1 Rcc8 26. Bxf7+ Kxf7 27. Ba7 bxa4 28. Bxb8 Rxb8 29. Rxa6 Rxe4 30. Rd7+ Ne7 31. g3 Rxb2 32. Rc7 Re2 33. Rxa4 Rb1#

Thomas Whittard lived on until the great age of 96, finally meeting his maker on 1 April 1919.

Obituaries in the local press reported on his church activities at great length.

This was one of the shorter tributes.

(The last sentence was incorrect: he left two sons and five daughters, and was predeceased by another son.)

The passive resisters, by the way, were those who, for religious reasons, refused to pay that portion of their taxes which would go towards funding Church of England schools.

That, then, was Thomas Whittard, a man whose remarkably long life was devoted, like so many of his generation and later, to public service, in his case mostly through preaching the Word of God. For many years, too, men (as they usually were) like Whittard also contributed to public service through their hobbies, becoming administrators and often benefactors as well as just participants. I think he deserves your remembrance.

But what of his young antagonist in our photograph, Walter Henry Rhodes Wisbey?

The name Wisbey comes from Essex, although perhaps its most famous bearer, at least to Brits of my generation, Great Train Robber Tommy Wisbey, came from a London branch of the family.

To find out more we need to travel east from Cheltenham, to the ancient town of Colchester.

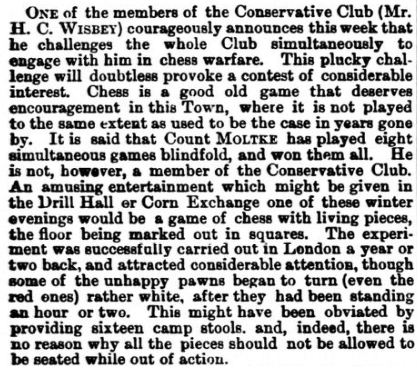

The 1880s was the decade where chess clubs as we know them today were starting to flourish. There was activity in surburban Essex, but little in the outlying towns.

Of course the local paper, as often happened, may have got his name wrong: the chess playing Conservative was probably JC, not HC Wisbey. John Chaplin Wisbey, to be precise. He did have an older brother, Henry Chaplin Wisbey, who doesn’t seem to have been a competitive chess player.

He faced 6 opponents, scoring 4 wins and a draw, and the resulting publicity sparked off a wave of chess interest in the town.

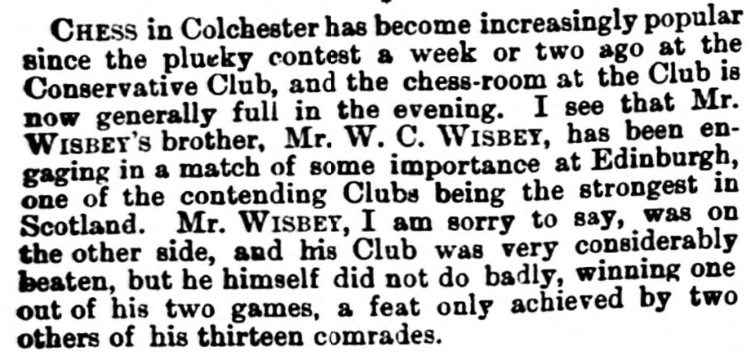

Here, we discover that John’s brother, Walter Charles Wisbey was also a chess player, based north of the border.

A club was soon formed, playing matches against other clubs in the area: from Chelmsford in the west to Clacton in the east (where they would have met James Kistruck) and Ipswich in the north.

A real chess addict, John was also playing correspondence chess through the Dublin Mail.

[Event “Dublin Mail Correspondence Ty”]

[Date “1889.??.??”]

[White “Wisbey, John Chaplin”]

[Black “Last, Charles William”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 g6 4. d4 exd4 5. Nxd4 Bg7 6. Be3 Nf6 7. Qd2 Nxd4 8. Bxd4 d6 9. O-O-O h5 10. Be3 Ng4 11. Bf4 Be6 12. Nb5 Ne5 13. Qc3 O-O 14. Qxc7 Qxc7 15. Nxc7 Rac8 16. Nxe6 fxe6 17. Bg3 Ng4 18. Rxd6 Nxf2 19. Bxf2 Bh6+ 20. Kb1 Rxf2 21. Bd3 Rxg2 22. Rxe6 Kf7 23. Rd6 Bf4 24. Rd7+ Kf6 25. Rxb7 Rxh2 26. Rxh2 Bxh2 27. Rxa7 g5 28. Rh7 h4 29. Be2 Rf8 30. a4 Ke5 31. a5 Kxe4 32. b4 Kf4 33. a6 Bg1 34. b5 Re8 35. Bc4 Rd8 36. Be6 Bf2 37. a7 Ra8 38. Rf7+ Kg3 39. Rxf2 Rxa7 40. Rf7 1-0

One of his regular opponents was Chelmsford top board Rev A Cyril Pearson, better known as a problemist.

[Event “Colchester v Chelmsford B1”]

[Date “1890.11.26”]

[White “Wisbey, James Chaplin”]

[Black “Pearson, Arthur Cyril”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4 4. Nxd4 exd4 5. O-O Bc5 6. d3 Ne7 7. Qh5 Bb6 8. Bg5 O-O 9. Nd2 c6 10. Bc4 Qe8 11. e5 Ng6 12. f4 Bd8 13. Ne4 Kh8 14. Rf3 d5 15. exd6 f6 16. f5 Ne5 1-0

Wisbey announced mate in 3: I’m sure you can find it for yourself.

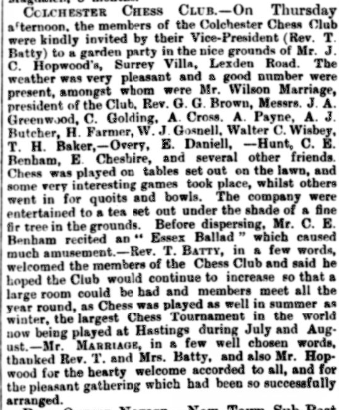

Here’s a report of a garden party held in 1895.

You’ll see that Walter had returned to the area, but John doesn’t seem to have been present. A month later, Walter resigned his membership as he was again moving away. We’ll catch up with him later. Wilson Marriage, later a Mayor of Colchester, was, as well as being a significant public figure, himself a strong player. He’s still remembered today by the residents of Wilson Marriage Road, and a school once used to bear his name.

In 1896, Wisbey struck up a friendship with a Sudbury player, Frederick Bull, a generation, if I’ve found the right man, his senior. Several of their informal encounters were submitted for publication.

Both men were bachelors, and there are indications that both were in fragile health. I suspect this was Frederick.

One would imagine their games and friendship brought them much satisfaction.

Wisbey, by now considered one of the strongest players in Esssex, usually won, but this loss was certainly entertaining.

[Event “Sudbury?”]

[Date “1896.??.??”]

[White “Bull, Frederick”]

[Black “Wisbey, John Chaplin”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. d4 f5 2. Bf4 e6 3. Nf3 Nf6 4. e3 Nc6 5. Ne5 Ne7 6. Bg5 h5 7. Be2 Ng4 8. h3 Nxe5 9. dxe5 g6 10. Nd2 Kf7 11. Nf3 Qe8 12. Nh4 Nd5 13. Bd3 Bb4+ 14. c3 Nxc3 15. bxc3 Bxc3+ 16. Kf1 Bxe5 17. Rb1 Bf6 18. Nf3 h4 19. Bxf6 Kxf6 20. Rb4 g5 21. e4 e5 22. exf5 Qh5 23. Rg4 Rg8 24. Qd2 d5 25. Nxh4 Bd7 26. Nf3 Rae8 27. Qc2 c6 28. Qc5 Bxf5 29. Bxf5 Kxf5 30. Rb4 Qf7 31. g4+ Ke6 32. Kg2 Ref8 33. Rb3 Qc7 34. Re1 e4 35. Nd4+ Kd7 36. Nf5 Re8 37. Kg1 b6 38. Qd4 Re5 39. Rbe3 c5 40. Qa4+ Kc8 41. f3 Rxf5 42. gxf5 Qg3+ 43. Kf1 Qxh3+ 44. Ke2 Qg2+ 45. Kd1 Kb8 46. fxe4 d4 47. R3e2 Qg3 48. Kc1 Qc3+ 49. Qc2 Qa3+ 50. Qb2 Qf3 51. Rf2 Qg4 52. e5 d3 53. Kd2 Qg3 54. Kc1 Rd8 55. Qd2 c4 56. Re3 Qg4 57. Qc3 Qg1+ 58. Qe1 Qxe1+ 59. Rxe1 c3 1-0

Here is one of his victories.

[Event “Sudbury?”]

[Date “1896.??.??”]

[White “Bull, Frederick”]

[Black “Wisbey, John Chaplin”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. c4 f5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Nc3 e6 4. e3 Bb4 5. a3 Bxc3 6. bxc3 Nc6 7. c5 Ne4 8. Bb2 Ng5 9. Bc4 Qf6 10. Nxg5 Qxg5 11. O-O O-O 12. f4 Qh6 13. Bb3 b6 14. cxb6 axb6 15. d4 Bb7 16. a4 Na5 17. Ba3 Rf7 18. Ba2 g5 19. fxg5 Qxg5 20. Qd2 Be4 21. Rf4 d5 22. Raf1 Rg7 23. Rxe4 fxe4 24. Qf2 Kh8 25. Kh1 Rag8 26. g3 Nb7 27. Bf8 Rxf8 28. Qxf8+ Rg8 29. Qf2 Nd6 30. Bb3 Nf5 31. Re1 Qh6 32. Kg1 Nh4 33. Bd1 Rf8 34. Qd2 Nf3+ 35. Bxf3 Rxf3 36. Qc1 Qg5 37. Re2 h5 38. Rf2 Rxe3 39. Rf8+ Kg7 40. Rf1 h4 41. Kh1 hxg3 42. Rg1 Kh7 43. Rg2 Kh6 44. hxg3 Rxg3 45. Qxg5+ Rxg5 46. Rf2 Kg7 47. Rg2 Rxg2 48. Kxg2 Kg6 49. Kf2 Kf5 50. Ke3 c6 51. Ke2 Kf4 52. Kd2 Kf3 53. Ke1 Ke3 54. Kd1 Kf2 0-1

The last record we have for John Wisbey playing chess was in May 1900, by which time he was on second board behind Marriage.

The 1901 census found him living (on his own means) with his sister’s family in Dovercourt, Harwich. Perhaps the seaside air would have been good for his failing health. He later moved to Fulham, where his death from TB was recorded four years later, at the age of only 42.

It’s to his brother Walter that we must now turn our attention.

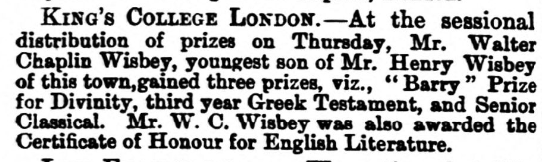

Walter was four years younger than John, so was only 21 when we found him playing in Scotland. He was by profession a schoolmaster who had just graduated from King’s College London.

At the time of the 1891 census he was teaching in Wolverhampton. After returning home he moved, in 1895, to London, where, according to an electoral roll for that year, he was teaching at Emanuel School. By 1898 he was in Cheltenham, where he married 20-year-old Jessie Rhodes. The following year Walter and Jessie’s first child, a daughter named Joyce Louise, was born in the Birmingham suburb of Handsworth. By 1905, when Walter junior, the boy in the photograph, arrived, they had moved to Southport, where we can pick him up as a member of the local chess club.

At some point he returned to Cheltenham – one wonders whether or not he was the mysterious ‘Walter’ in their 1908 match against Oxford University. Then, on 3 December 1910, he died there at the age of 44.

His death record tells us he died in the local Lunatic Asylum from ‘dementia and general paralysis’, which, in those days, was often the result of untreated syphilis. It also gives his occupation as ‘former monumental manager’, so perhaps he’d left his teaching job. The burial service was conducted by another Cheltenham Chess Club member, Rev Hubert Evan Noott (no relation to Rev Mervyn Noote).

His older brother Henry had died of something very similar (I’d guess also syphilis) at the age of 50 in 1902, as had Harry Nelson Pillsbury in 1906.

A strange and relatively short life, then. What was with all this moving from school to school every couple of years? I guess we’ll never know.

Walter junior had, we’re told, been playing chess for three years when playing Thomas Whittard at the 1913 British Championships. His father had died almost three years earlier, having been ill for 17 months, according to his death certificate. It is perhaps unlikely that he would have been well enough to teach his son the moves, but the family were clearly connected with the wider chess community in Cheltenham. Maybe a family friend taught him to play, thinking the game might help him keep his mind off his father’s illness.

They would probably have known Whittard, along with Rev Noott, who officiated at his funeral, and perhaps another Cheltenham chess player, a photographer named Alfred William Martyn. Be careful not to confuse him with his more celebrated first cousin, Alfred Willie Martyn, also from Cheltenham.

He took part, without success, in the Second Class A section, losing this game: you can read about his opponent’s family here.

[Event “BCF-ch 10th Second Class A R8”]

[Date “1913.08.19”]

[White “Martyn, Alfred William”]

[Black “Beamish, Ferdinand Uniacke”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. d3 d6 5. c3 Bd7 6. Nbd2 g6 7. Nf1 Bg7 8. Ng3 O-O 9. Bg5 h6 10. Be3 Kh7 11. h3 Ne8 12. Nh2 f5 13. exf5 Bxf5 14. Nxf5 Rxf5 15. Ba4 d5 16. d4 Qd6 17. Bc2 Rf7 18. O-O Nf6 19. f4 exd4 20. cxd4 Re8 21. f5 g5 22. Rf3 Ne4 23. a3 Ref8 24. g4 Qf6 25. Bxe4 dxe4 26. Rf2 Nxd4 27. Rb1 Qd6 28. Kg2 c5 29. Qa4 b6 30. Rd1 Qc7 31. Qa6 Rd8 32. Rfd2 Rd6 33. Qf1 Be5 34. Qh1 Rfd7 35. Nf1 Nf3 36. Rxd6 Rxd6 37. Nd2 Qd7 38. Nxf3 exf3+ 39. Kxf3 Rxd1 40. Qg2 Qd5+ 41. Kf2 Qxg2+ 42. Kxg2 Bxb2 43. a4 Bd4 44. Kf3 Rd3 0-1

Martyn’s wife Alice died in the fourth quarter of 1917, and, with what might be considered rather unseemly haste, he married Jessie Wisbey in the first quarter of 1918. The 1921 census found them in Cheltenham, with Jessie’s two and Alfred’s three children, along with his mother and 3-year-old Eric Latimer Saunders, who doesn’t seem to have been related to either Alfred or Jessie.

What I’m sure you want to know is whether young Walter continued his childhood interest in chess. The answer, unfortunately, is that, despite his early start, there’s no record of his ever having played competitively. I do hope he continued playing socially, though.

There’s really not much else to report. He married a much younger woman, Rosalind Nelmes, in Newport, Monmouthshire in 1937, briefly saw war service as a surveyor in the Royal Engineers, and his death was recorded in Ipswich, not too far from his father’s home town, in 1993. Rosalind outdid even Thomas Whittard, dying, again in Suffolk, in 2017 at the age of 99. They had, as far as I can tell, no children.

So you could say that, via a marriage, the photograph of Thomas and Walter playing chess in 1913 takes us from 1822 through 195 years almost to the present day. A picture that really does paint a thousand words, and almost 200 years.

I think we need to stay in Cheltenham a little while longer. Join me soon for some more Minor Pieces.

Sources and Acknowledgements

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archives

General Register Office (GRO) death records

Wikipedia

BritBase (John Saunders)

Chess Book Chats (Michael Clapham)

Grace’s Guide

Leave a comment