Looking for problems to include in a future Chess Heroes book, I chanced upon this, by a composer previously unknown to me.

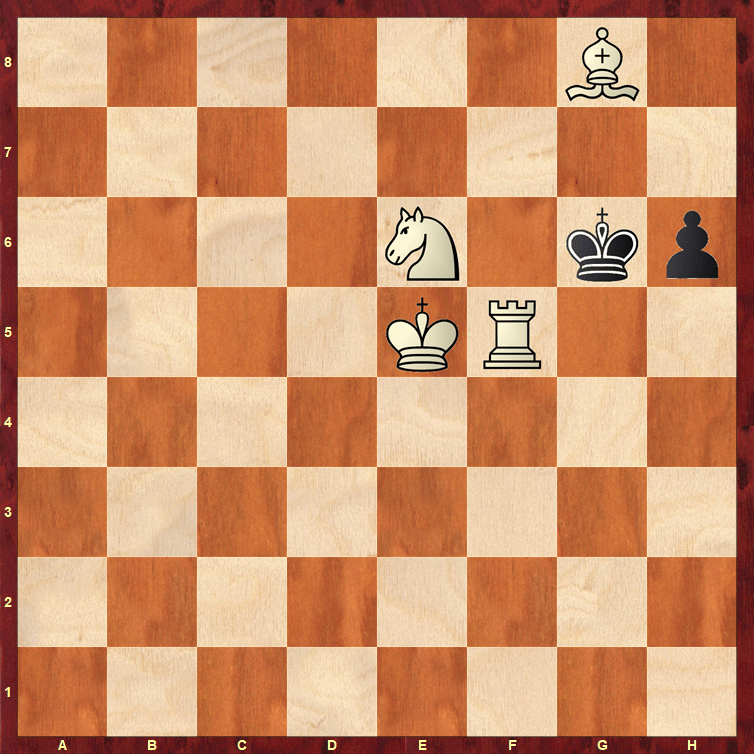

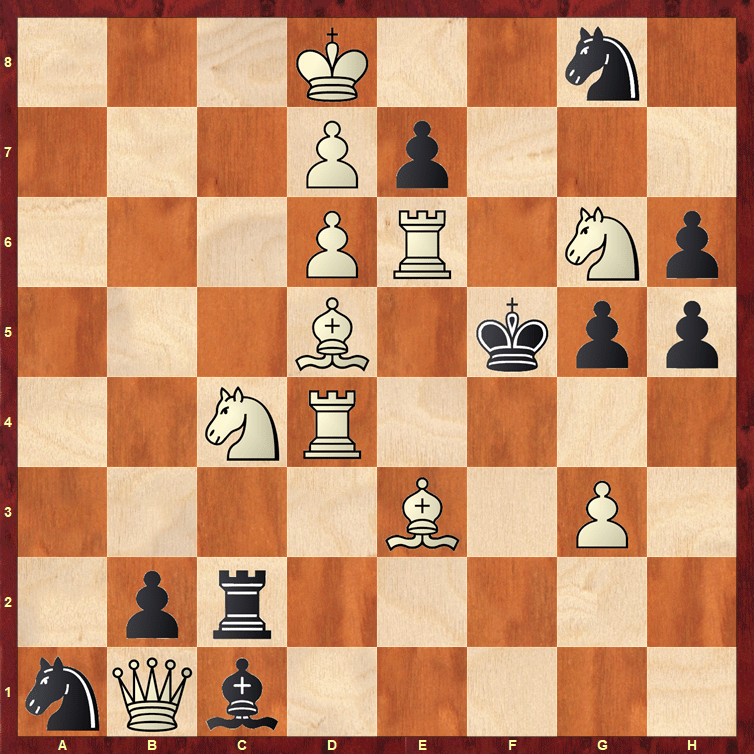

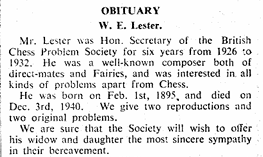

#2 Miss Rose Marsden

The Tablet, 14 Nov 1925

Of course I wanted to find out more about Rose, and I’m sure you do too. Was she perhaps a child prodigy, following in the footsteps of Lilian Baird a generation earlier? Or maybe she was a lady of a certain age and class involved with the Imperial Chess Club. Nothing could be further from the truth than either of those speculations.

Join me now as we visit Billingsgate Fish Market in the early spring of 1891, where the foul stench of the fish is matched only by the foul language of the porters. For many years Billingsgate was a byword for loud and abusive language. It’s one of those fish porters, Henry Isaac Marsden, we are here to meet.

On census day, Sunday 5 April, we visit his house at 90 Armagh Road, Bow, some 3½ miles or so away from Billingsgate. There are flats there now, just west of the Olympic Stadium and south of Victoria Park, but this would have been a small Victorian terraced cottage. Did he walk to work or take the train? 11 year later his journey would become easier with the opening of the Upminster branch of the District Railway, with a new station at Bow Road. Henry, or Harry as he preferred to be known, and his wife Emily are both aged 29, sharing their home with four daughters, Emily junior (11), Alice (9), Ellen (8) and Louisa (3). Except that they’re not his daughters.

Emily had previously been married to an Irish labourer named Michael Cleary, who was the girls’ father. It’s not at all clear where Michael was in 1891, but it was quite possible that her relationship with Henry Marsden was bigamous.

Emily is heavily pregnant, and just four days later another daughter would be born, given the name Rosetta. Unlikely as it may seem, Rosetta, the fish porter’s daughter, grew up to become a published chess problemist.

Let’s follow the family forward. By 1901 they’d moved round the corner, to 25 Appian Road, where Henry was still a fish porter in the market. They now had five children of their own: Rosetta had been joined by Henry George, Lily, Florence Violet and Daisy May. You’ll notice that, in the fashion of the time, the girls all had charmingly floral names. Louisa was also still at home, as was Ellen, who had reverted to Cleary.

Ten years on, and they’d moved to 82 Libra Road, still on the same estate. Florence and Daisy were still at school. Lily had left, but not yet found a job. Henry junior was an office lad, and Rosetta was employed in a confectionery works. Henry senior was yet again, as he would be in 1921, described as a fish porter.

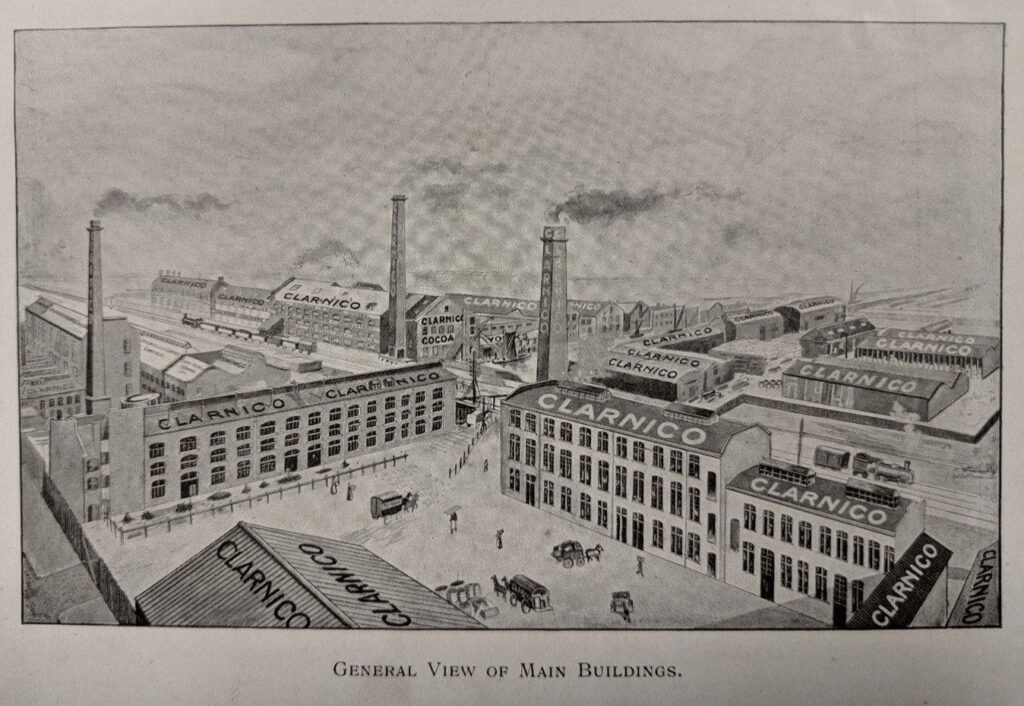

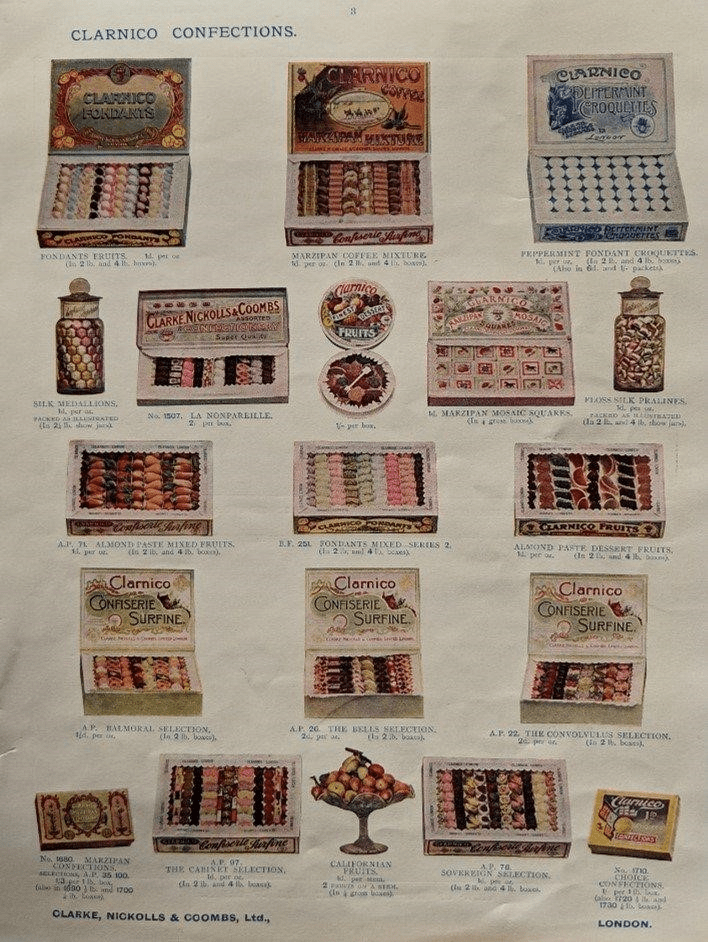

The confectionery works would have been Clarnico, the trading name of Clarke, Nickolls & Coombs Ltd, taken from the first letters of their names. One of the largest confectionery companies of their day, their factory in Hackney Wick was a mile or so away from Rosetta’s family home.

The area is now part of the Olympic Park, and the area’s industrial heritage is referenced in the new Sweetwater development. Clarnico Lane today marks the spot.

Here, from 1906, about the time Rosetta would have started working there, you can see a selection of their delicious wares.

According to the Hackney Bridge website:

In its heyday, not only was it the largest sweet factory in the country, but it was also ahead of its time when it came to the welfare and wellness of its employees. Before it was popular to practise corporate social responsibility, they established social groups, built a rehabilitation facility, and even ran their own fire and ambulance service for the neighbourhood.

In addition, thanks to the generosity and friendliness of the founders, many unmarried women preferred to work here as the terms of their employment were considerably more beneficial than at other contemporaneous enterprises.

It was there, between the fondant fruits and the peppermint croquetttes, that Cupid fired his arrow, and Rosetta met the love of her life.

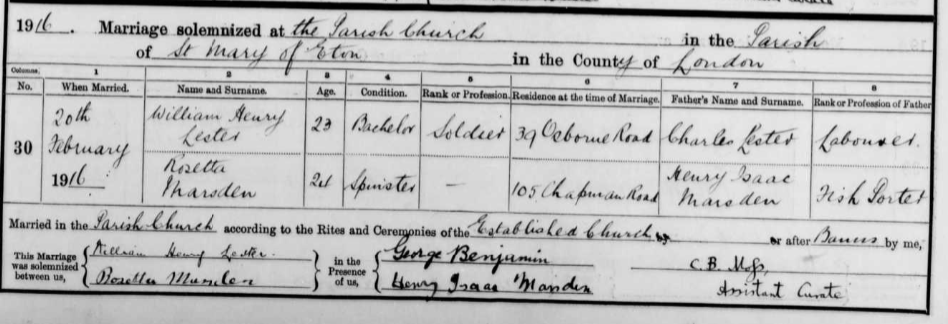

St Mary of Eton was – and still is – of considerable interest.

In the late 19th century, Eton College launched a scheme to provide social and religious support to people living in the crowded district of Hackney Wick in east London, and to familiarise privileged schoolboys with social conditions in deprived areas. The project of establishing an “Eton Mission” was started in 1880. St Mary of Eton Church was built 1890-02 as the centrepiece of the mission.

We need to meet William Henry Lester.

His family was, on his father’s side, originally German, named Leister, but the ‘i’ was gradually, and understandably giving the climate at the time, dropped.

He was a couple of years younger than Rosetta, having been born in Southwark, south of the river, on 1 February 1893. We can pick his family up in the 1901 census, living in 190 Chrisp Street, in the Parish of St Gabriel South Bromley, one of the poorest areas of the East End, where his father Charles had found work as a timekeeper in a fish factory.

Here’s local historian and parish priest Arthur Royall (1919-2013):

The Parish Church of St. Gabriel, South Bromley, was in the Anglo-Catholic tradition as were many other Church of England parishes in East London, the colourful ritual of such churches appealed to many forced to spend their lives in a grey and dismal area deprived of all visual beauty. Served for the most part by outstanding and devoted priests who sought to provide for both the spiritual and material needs of the parishioners, such churches were accepted as a normal part of the pattern of East London life.

St. Gabriels was consecrated on 22nd. February 1869. The population of the new parish was 7,000 crowded into a small area of what has been described as mean streets, a later pre-1914 writer speaks of houses “packed like bricks in a box, and the roads are characterless, whilst London’s pall of smoke is over everything”.

Writers about East London around the turn of the century had a tendency to pile on the agony, especially if they were seeking financial support for a much needed social or religious project, however accepting this , there is no doubt that the description of it as an “unlovely district”, the dwellers in which were among “the poorest toilers in London” was reasonably accurate.

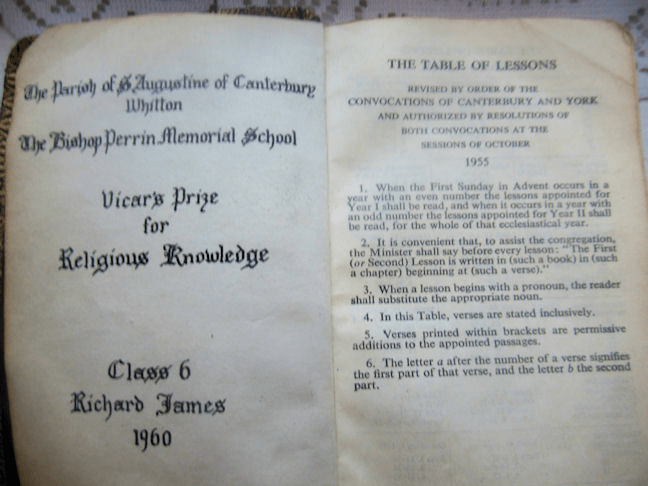

(As an entirely coincidental aside, back in 1959 I used to know Arthur Royall and his family very well. He was our parish priest at St Augustine of Canterbury Whitton at the time, presenting me with this prayer book.

In 1964 he chose to move to Poplar to continue his ministry in London’s East End. His sons Robert and Richard were roughly the same age as my brother and I.)

By 1911, now Lester rather than Leister, William’s family had moved to Osborne Road, Hackney Wick, a short walk from the Clarnico works, where two of the family had found employment. Charles was now working as a general labourer. He and his wife Annie had had nine children, two of whom had died. The seven surviving children, six boys and a girl,By were all still at home. Their eldest son, also Charles, was working as a wood wool cutter, shaving logs into fibres, while William and his brother Alfred were both at Clarnico, the former as an entering clerk and the latter as a tinsmith.

William was a highly intelligent young man who was moving from the manual labour of the working classes to the office work of the new and burgeoning middle classes. One wonders if he had won a scholarship to the local Coopers’ Company School where he would have been a near contemporary of Jack Warner (Dixon of Dock Green).

By 1916, though, he’d left Clarnico to serve his country, while Rosetta had left to get married.

We can pick them up again in the 1921 census, living in Chapman Road. William was now a Civil Servant, working in Whitehall, a temporary clerk in the Department of Education. He’d remain a Civil Servant all his life, later transferring to Customs and Excise. Rosetta was at home, looking after their two children, 2 year old Doris Rosetta, and a baby son, who, a few days later, would be baptised with the names Leslie William Edward. The following year, their second son and youngest child, Cyril William, would join the family.

William must have been fond of his first name, but didn’t much care for Henry, preferring to be known as William Edward Lester, the name by which he would achieve a modicum of fame.

He was a man who enjoyed puzzles of all sorts, and was attracted to the chess problems he saw in the newspapers. I wonder where and when he learnt the game. Did his father teach him, did he learn at school, or from reading books?

By 1921 his name was appearing in newspaper chess columns both as a solver and as a composer. He was also, at least from 1922, editing a chess column in the Civil Service magazine Red Tape.

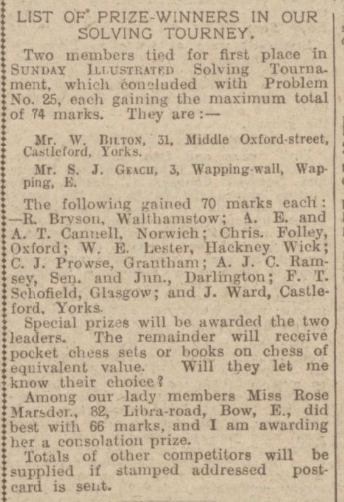

It wasn’t just William, though. He must have taught Rosetta, or Rose as she preferred to be known.

You’ll note that, although she was married, she preferred to use her maiden name, perhaps to avoid any suspicion that her husband might have helped her. She may have been using her parents’ address for the same reason. Libra Road, by the way, ran parallel to Armagh Road, where she had been born 30 years earlier. Only a small part of it is still in existence.

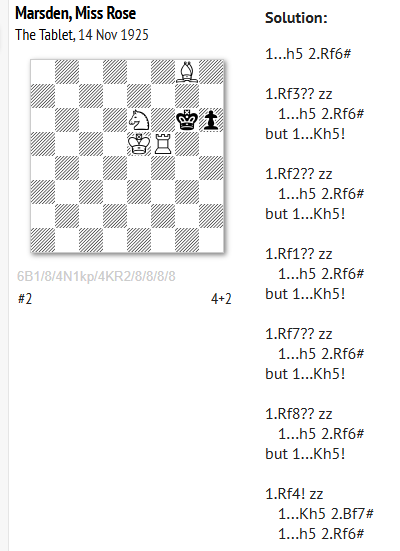

Here’s an early problem from William: a prize-winner from the other side of the world.

#2 Lester, William Edward

2nd Prize The Brisbane Courier, 30 Jun 1923

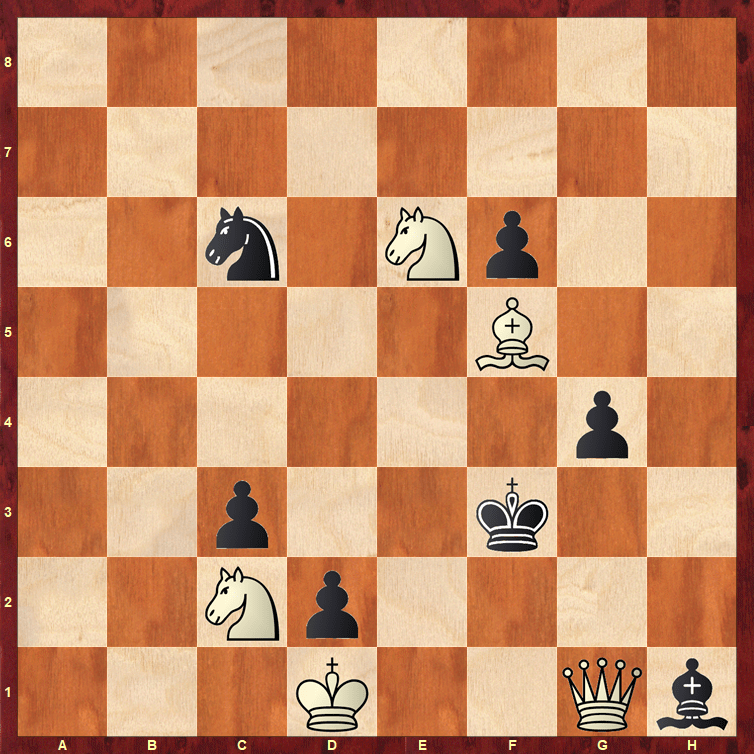

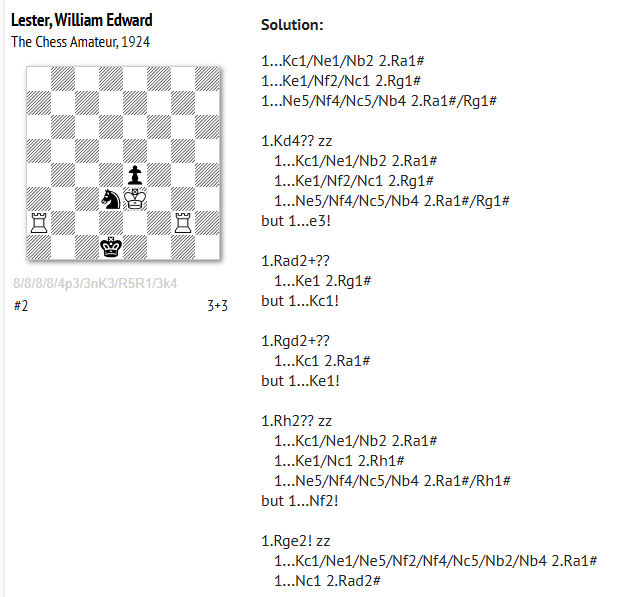

In 1924, Lester published a lot of lightweight problems in The Chess Amateur. Here’s one of them.

#2 Lester, William Edward

The Chess Amateur, 1924

Meanwhile, Rose wasn’t only composing chess problems: she was compiling crosswords as well. Between 1925 and 1927 she had several crosswords published in the London Evening News, receiving a fee of 2 guineas for their publication. William must have been sharing his love of puzzles of all sorts with his wife. Again, she was using her maiden name and her parents’ address for this endeavour.

Unfortunately, though, I haven’t been able to discover any more puzzles in her name.

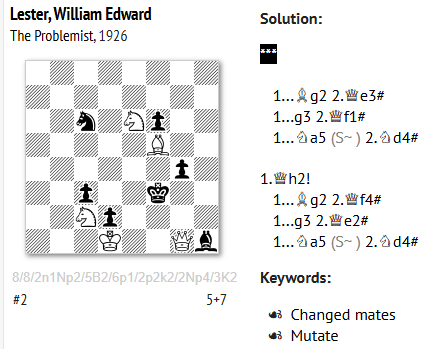

In January 1926 the British Chess Problem Society launched the first issue of a new bi-monthly publication: The Problemist, still going strong a century on.

William was already the Assistant Secretary of the society, and was one of the contributors to the inaugural issue.

#2 Lester, William Edward

The Problemist, January 1926

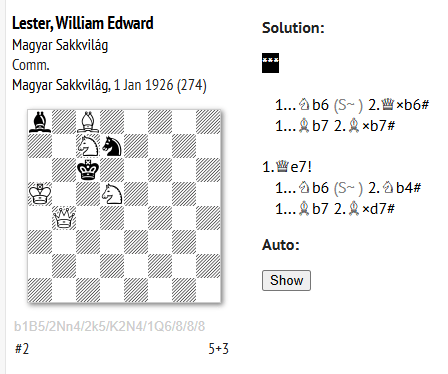

At the same time, this problem was also honoured.

#2 Lester, William Edward

Comm. Magyar Sakkvilág, 1 Jan 1926

In 1927, following the resignation of the Rev Noel Bonavia-Hunt, Lester was appointed Secretary of the British Chess Problem Society, a tribute to his organisational ability. He was also giving lectures to the society members, demonstrating his favourite problems.

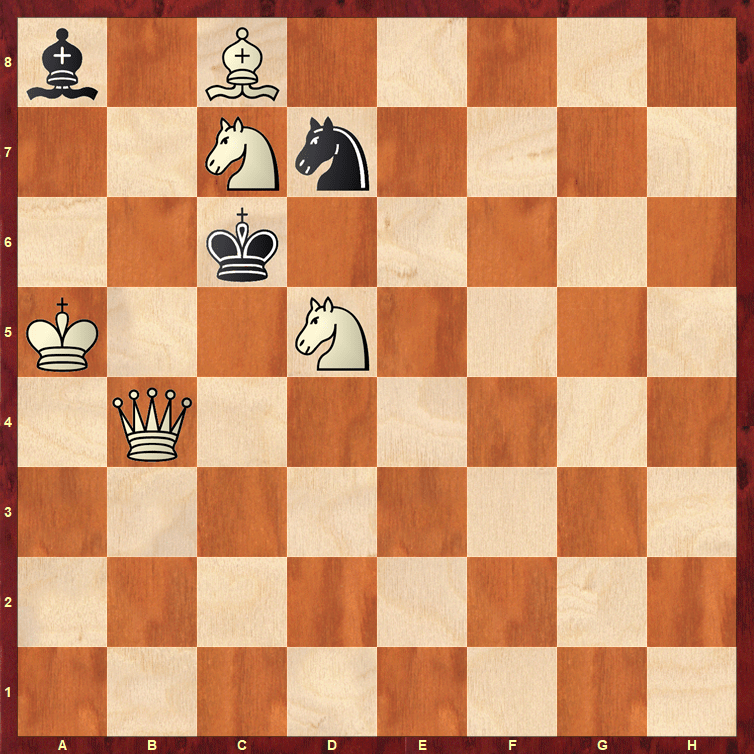

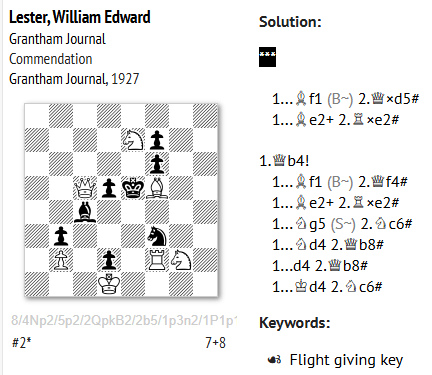

This 1927 problem also received a commendation.

#2 Lester, William Edward

Commendation Grantham Journal, 1927

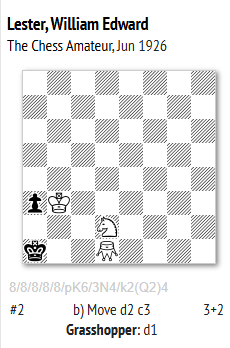

By now, Lester had struck up a friendship with the great Thomas Rayner Dawson, and developed an interest in Fairy Chess (using different pieces or stipulations) problems.

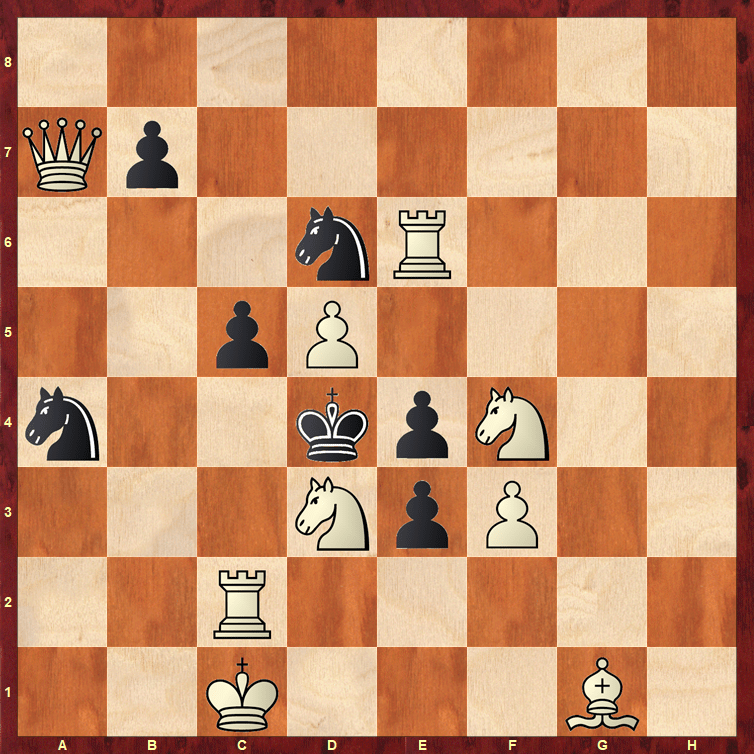

One of the most popular fairy pieces was the Grasshopper, which moves on queen lines, but only by hopping over a piece of either colour, landing on the next square, and, if there’s an enemy piece there, capturing it.

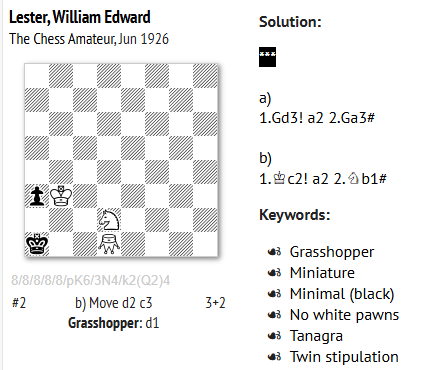

Here’s an example: Problem 7.

This is a twin: when you’ve solved it you move the knight from d2 to c3 and solve it again.

The 1930s seem to have been a quiet time for William, Rose and their family. William continued composing, though not prolifically, and they were able to move out to 32 Chesterfield Road, Leyton, some three miles to the north.

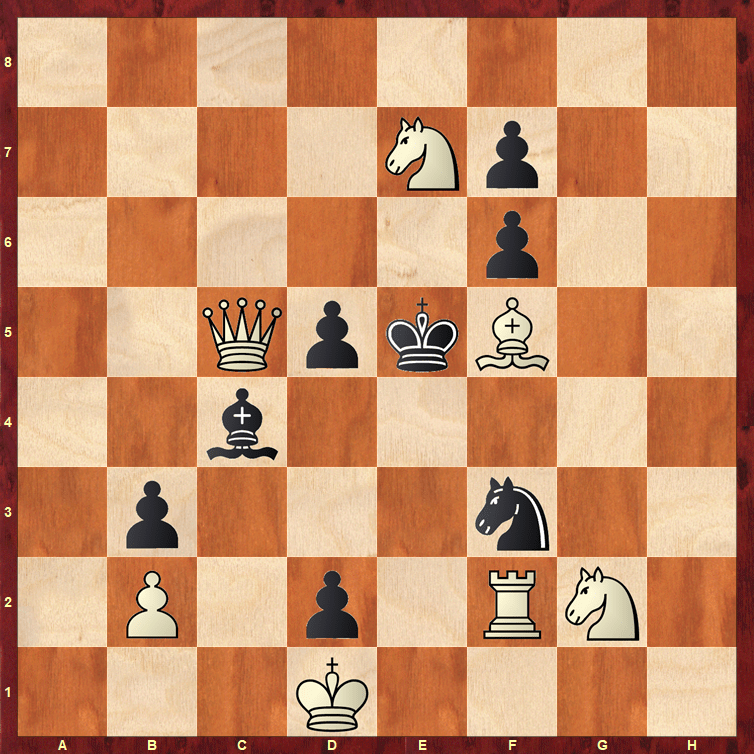

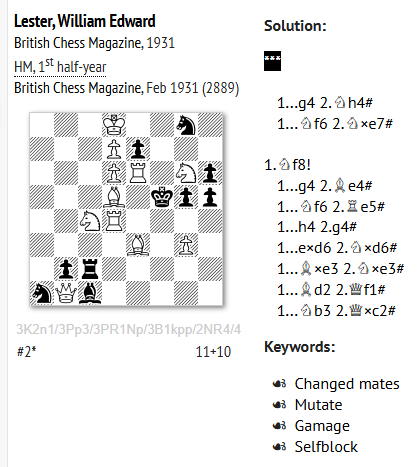

Although he was composing mostly Fairy Chess problems by now, this orthodox mate in 2 received an honourable mention.

#2 Lester, William Edward

HM, 1st half-year British Chess Magazine, Feb 1931

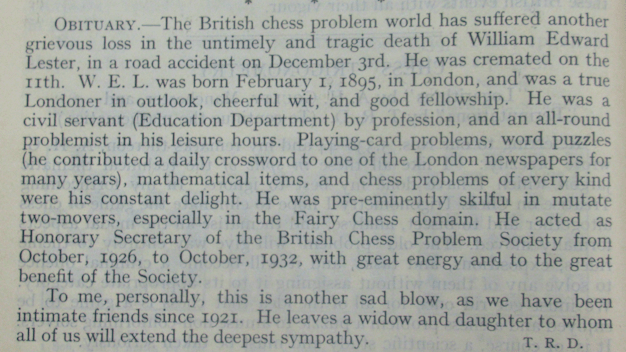

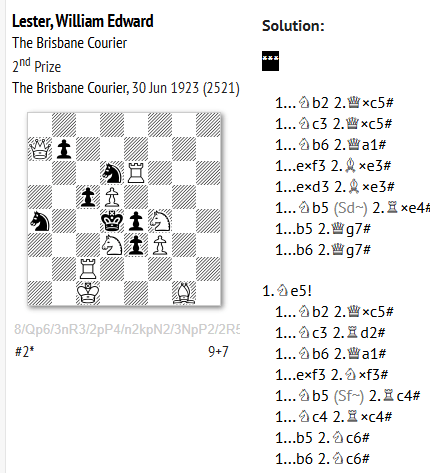

Sadly, William’s life came to a premature end in December 1940. His friend TR Dawson paid tribute.

Two things: he’d moved to Customs & Excise by the 1939 Register, and it’s strange that Dawson failed to mention his sons as well as his daughter.

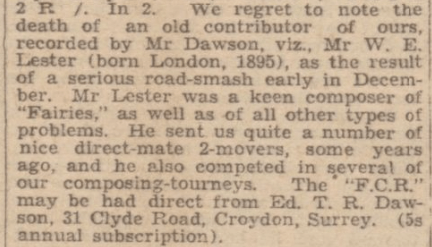

His death was also recorded in the Falkirk Herald.

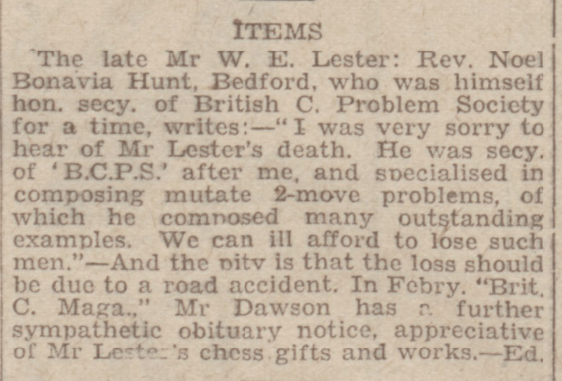

Two weeks later his former colleague Noel Bonavia-Hunt offered his tribute.

The Problemist had surprisingly little to say – and again failed to mention his sons.

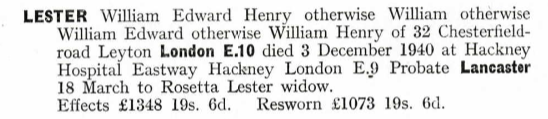

His probate record suggests that he didn’t leave a lot of money: perhaps he never rose all that far up the Civil Service ladder.

Rose seems to have retired to Southend, where she died in 1962. Cyril died in 1992, Doris in 2006, and Leslie, at the age of 96, in 2018.

The story of William and Rose is one of social mobility. William Lester grew up in one of London’s poorest streets, the grandson of a German immigrant, but became a leading light of the British Chess Problem Society, a ‘true Londoner’, renowned for his ‘cheerful wit’ and ‘good fellowship’. He would have been drawn to chess, perhaps, by the problems regularly published in newspapers at the time, and it was the puzzle element rather than the competitive element that appealed to him most about our wonderful game. He was also able to share his love of chess problems – and crosswords – with his wife, who herself became a published problemist.

You might see some parallels with the bus driving Gunning brothers, who also, despite their humble origins, became successful chess problemists. Even the rarefied world of chess compositions can, if promoted in the right way, bring together people from very different backgrounds.

As always, join me again soon for some more Minor Pieces: forgotten stories from the world of chess.

Acknowledgements and Sources

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

MESON chess problem database: Lester here.

Yet Another Chess Problem DataBase (YACPDB): Lester here.

British Chess Problem Society website/The Problemist

Hackney Bridge website

Arthur Royall website

Colin Pykett website

Mayhematics (George Jelliss)

Problem Solutions (copied from YACPDB)

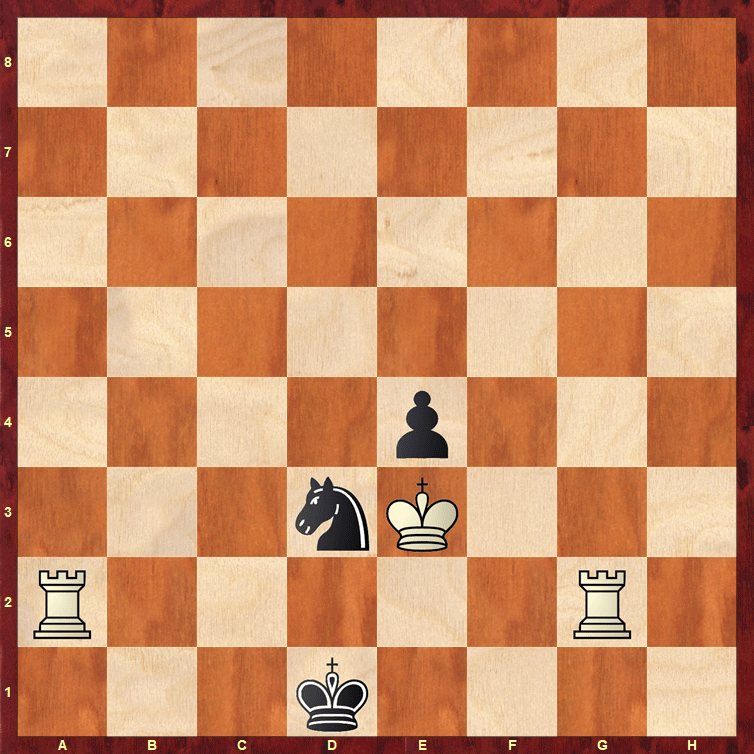

Problem 1:

Problem 2:

Problem 3:

Problem 4:

Problem 5:

Problem 6:

Problem 7:

Problem 8:

Leave a reply to Chess Puzzle of the Week (349): Solution – Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club Cancel reply