The 1920s saw the beginnings of chess competitions for juniors. In 1921 a boys’ tournament took place in Hastings: this was repeated in 1922 and by 1923 had become the official British Boys’ Championship, for those under the age of 18. The first winner was Philip Stuart (later Sir Stuart) Milner-Barry.

That year the London Chess League decided to run their own championship for boys, starting on 31 December 1923, so you might just about claim that 2024 marks its centenary. It’s still going strong under the name of the London Junior Chess Championships.

The tournament took place, along with two sections for adult players, at St Bride’s Institute, which would remain its venue for many years. Sir Richard Barnett, whom you met last time playing chess on a liner in 1930 before sailing off into the sunset, was on hand to open the congress, advising the contestants to put ‘safety first’.

In these days of pre-teen grandmasters and an 18-year-old world champion, it’s salutary to consider how, just a century ago, the whole idea of teenagers playing chess was considered strange. The press commented on how well they played, and on how they used up most of their time on the clock.

The tournament attracted ten players, and press interest was such that we have all their initials and surnames, and, in some cases, their schools. Of course it doesn’t help that one of the competitors was J Smith, but we can at least have a stab at identifying all of them. While most of them grew up to have fairly anonymous lives (mostly) away from the chessboard, two of them had more interesting stories to tell, one inspirational, the other disturbing.

The first story I’d like to tell is that of Max Black. Born in 1909 and a pupil at Dame Alice Owen’s School in North London, he was one of the younger competitors. In spite of his relative youth he scored 6/9, finishing in third place.

Max’s father Lionel was a wealthy Jewish silk merchant, born in Kyiv, but, by 1909 living in Baku where Max (like Garry Kasparov many years later) was born. In 1912, deciding that Russia wasn’t a safe place for a Jewish family, Anglophile Lionel, his wife and two young sons (Max had now been joined by Misha) moved to England, translating their name from the Russian Tcherny to Black. Two more children would be born there: Samuel (Sam) and Rivka (Betty).

Here, in a family photo from an online tree, you can see the family at some point in the mid 1920s.

Max played in the London Boys’ Championship for the next three years (I’ll tell you how he fared another time) before graduating to adult chess in 1928. By this time he was reading mathematics at Queens’ College Cambridge, and was also moving in the same circles as the leading philosophers of the day, such as Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

He was selected to play on board 5 in that year’s Varsity match, where he faced future Communist spy Solomon Adler.

He was losing for much of the game, but, after Adler made an instructive error just before adjudication, he was fortunate to be able to share the point. (As always, copy and paste the pgn here to play through the game online.)

[Event “Cambridge Univ v Oxford Univ B5”]

[Date “1928.03.23”]

[White “Black, Max”]

[Black “Adler, Solomon”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 e6 3. c4 Bb4+ 4. Bd2 Bxd2+ 5. Nbxd2 d5 6. e3 O-O 7. Bd3 Nbd7 8. O-O b6 9. cxd5 exd5 10. Qc2 Bb7 11. Ne5 h6 12. f4 Rc8 13. Ndf3 Nxe5 14. fxe5 Ne4 15. Rad1 c5 16. Qb1 c4 17. Bxe4 dxe4 18. Nd2 c3 19. bxc3 Rxc3 20. Nxe4 Rxe3 21. Nd6 Bd5 22. Rf5 Re2 23. Rf2 Bxa2 24. Qa1 Rxf2 25. Kxf2 Qh4+ 26. Kg1 Bd5 27. Qc3 Bxg2 28. Rd3 Bd5 29. Rg3 Qf4 30. Nc8 Qe4 31. Ne7+ Kh7 32. Nxd5 Qxd5 33. Qd3+ g6 34. h4 Rd8 35. Rg4 Qxe5 36. Qxg6+ fxg6 37. dxe5 Re8 38. Re4 Re7 39. Kf2 Kg7 40. Ke3 g5 41. hxg5 hxg5 42. Kd4 Rd7+ 43. Kc4 Kg6 44. e6 Re7 45. Kd5 1/2-1/2

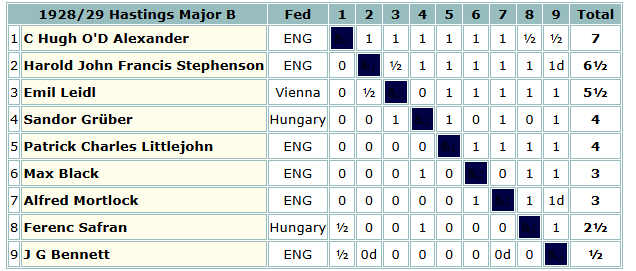

Max entered the 1928-29 Hastings Congress where he was placed in the Major B section, won by his contemporary C H O’D Alexander.

He lost this game against another talented teenager, where he made a couple of understandable defensive errors against Mortlock’s kingside attack.

[Event “Hastings Major B”]

[Date “1928.12.??”]

[White “Black, Max”]

[Black “Mortlock, Alfred”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 exd4 4. Bc4 Bc5 5. O-O d6 6. c3 dxc3 7. Nxc3 Nf6 8. Bg5 h6 9. Bh4 Be6 10. Bxe6 fxe6 11. Qb3 Qc8 12. Rae1 e5 13. Bxf6 gxf6 14. Nd5 Rf8 15. Nh4 Bb6 16. Qf3 Qe6 17. Qh5+ Rf7 18. Qxh6 O-O-O 19. Nf5 Rg8 20. Qh3 Kb8 21. Qd3 Rh7 22. a4 Rgh8 23. h3 Qf7 24. b4 Qg6 25. Nxb6 Rxh3 26. Ng3 Qh6 27. f4 exf4 28. gxh3 Rg8 29. Nd7+ Kc8 30. Kf2 Rxg3 31. Qd5 Qxh3 32. Nb6+ Kb8 33. Nd7+ Ka8 34. Nb6+ axb6 35. Ke2 Rg2+ 36. Kd1 Qc3 0-1

In the matches preceding the 1929 Varsity Match Max won two games against Maurice Goldstein, one of the strongest London amateurs of his day.

Here’s one of them.

[Event “Combined Universities v London University”]

[Date “1929.03.16”]

[White “Black, Max”]

[Black “Goldstein, Maurice Edward”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 e6 3. c4 c5 4. d5 b5 5. b3 exd5 6. cxd5 Bb7 7. Bb2 Nxd5 8. Nc3 Qa5 9. Qd2 Nf6 10. e3 b4 11. Nb5 Ne4 12. Qd1 a6 13. Ne5 axb5 14. Qh5 Nd6 15. O-O-O Ra6 16. Rxd6 Bxd6 17. Nxf7 O-O 18. Ng5 Be4 19. Nxe4 Be7 20. Bd3 Rh6 21. Qe5 Bf6 22. Qd5+ Kh8 23. Nxf6 gxf6 24. Qg5 Rg6 25. Bxg6 hxg6 26. Qh6+ Kg8 27. Qxg6+ Kh8 28. Bxf6+ Rxf6 29. Qxf6+ Kh7 30. Qf5+ Kg7 31. Qe5+ Kh7 32. Qxb8 Qxa2 33. Qe5 Qxb3 34. Qxc5 Qa3+ 35. Kd2 Qa2+ 36. Qc2+ 1-0

It’s interesting to observe in these games that players were experimenting with openings (the Pirc Defence and the Benko Gambit) which would only become established several decades later.

In the Varsity Match itself he again faced Solomon Adler, this time getting crushed with the black pieces after playing the opening much too passively.

[Event “Cambridge University v Oxford University B4”]

[Date “1929.03.23”]

[White “Adler, Solomon”]

[Black “Black, Max”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 d6 2. d4 Nf6 3. Nc3 g6 4. Nf3 Bg7 5. Be2 O-O 6. O-O b6 7. Bf4 Bb7 8. d5 Nfd7 9. Qd2 Re8 10. Bh6 Bh8 11. Ng5 Nf6 12. f4 e6 13. dxe6 fxe6 14. f5 exf5 15. Bc4+ d5 16. Nxd5 Nxd5 17. exd5 Qd6 18. Ne6 Na6 19. Rxf5 gxf5 20. Qg5+ Kf7 21. Qxf5+ Kg8 22. Qg5+ 1-0

Max’s next appearance was in the 1930 Varsity Match, by which time he’d reached the heights of Board 2, facing (Arthur) Eric Smith.

Again, he was lucky to escape with a draw after the future Canon missed a couple of wins.

[Event “Cambridge University v Oxford University B2”]

[Date “1930.03.22”]

[White “Smith, Arthur Eric”]

[Black “Black, Max”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Nf3 Nbd7 5. Bg5 c6 6. e3 Qa5 7. Nd2 Bb4 8. Qc2 O-O 9. Bxf6 Nxf6 10. Bd3 Re8 11. O-O e5 12. dxe5 Rxe5 13. Nf3 Rh5 14. Ne2 Bd6 15. h3 g5 16. Ng3 Bxg3 17. fxg3 g4 18. Nh4 dxc4 19. Bxc4 Qe5 20. Qf2 Kg7 21. Rad1 Be6 22. Bxe6 Qxe6 23. Nf5+ Kg6 24. Nh4+ Kg7 25. Nf5+ Kg6 26. Nh4+ Kg7 27. Qf4 Nd5 28. Qd4+ Kg8 29. e4 Ne7 30. Rf6 Qe5 31. Qf2 Rf8 32. Rf1 Qc5 33. hxg4 Qxf2+ 34. R1xf2 Re5 35. R2f4 Ng6 36. Nxg6 hxg6 37. Kf2 Kg7 38. Rd6 Rb5 39. b3 a5 40. Rd3 a4 41. Ke3 Ra5 42. Rd7 1/2-1/2

But that was to be the end of his competitive chess career, as, on completing his studies he chose to devote himself to his academic and family life.

After graduating in 1930 Max spent a year studying in Göttingen, before taking a post teaching mathematics at the Royal Grammar School in Newcastle, at the same time writing his first book, The Nature of Mathematics: a Critical Survey. In 1936 he returned to London, lecturing in maths at the Institute of Education (part of University College London). In 1940, switching from maths to philosophy, he accepted a post at the University of Illinois, before becoming a philosophy professor at Cornell University in 1946. He remained at Cornell until his retirement in 1977, but continued lecturing worldwide until his death in 1988.

Describing himself as a “lapsed mathematician, addicted reasoner, and devotee of metaphor and chess”, he maintained an interest in chess throughout his life. He is particularly noted for the ‘mutilated chessboard’ problem, devised as means of demonstrating critical thinking. Take a chessboard with two opposite corners removed. Is it possible to fill the whole board with 2×1 dominoes? If you stop and think for a moment, the solution is obvious, but not everyone is able to think like that.

His celebrity chess opponents included Arthur Koestler, whom he beat in four moves, and Vladimir Nabokov, whom he beat twice, neither game lasting more than 15 minutes. It’s said that he gave displays of blindfold chess and, even in his late sixties, gave simultaneous displays against up to 20 opponents.

I would suggest to you that, as an analytical philosopher, searching for meaning in language, mathematics, science and art, promoting logic and critical thinking, Max Black was one of the most important figures of the 20th century you probably haven’t heard of. It’s gratifying to know that, in his teens, he took part with distinction in the first four runnings of the London Boys’ Chess Championship.

If you’re interested you can read more about him on Wikipedia and MacTutor. You’ll find lots more online as well: Google Books and Amazon Books are both helpful.

His brothers both achieved eminence as well, in very different fields. Sir Misha Black, who wasn’t a competitive chess player, was an architect and designer noted for the street signs in Westminster and for designing trains for British Rail and the London Underground. Sam Black, the youngest of the three brothers, was also an alumnus of the London Boys’ Chess Championship, and had a very distinguished international career in the field of public relations while at the same time practising as an optician. A lifelong chess player, he was Secretary of Finchley Chess Club and President of the North Circular Chess League, who still run an annual blitz tournament in his honour.

While Misha Black was campaigning for peace in the 1930s, one of Max’s opponents was following a very different path.

Clement Frederic Brüning , as the youngest player in the competition, attracted some media attention.

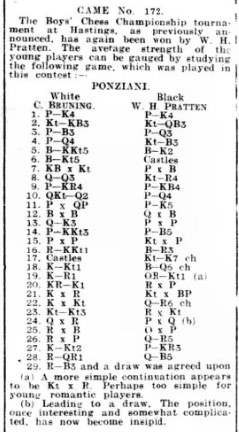

He finished in last place, with a score of 2/9, but, undaunted, he also took part in the British Boys’ Championship a few months later, drawing with the eventual winner Wilfred Pratten in his preliminary group and finishing runner-up to Alfred Mortlock in his section of the finals.

Like Max Black, Clement came from an immigrant background. While Max was the oldest child of Russian Jewish parents who were first generation immigrants, Clement was the youngest of five sons of a German Catholic father and an English mother.

Carl Alexander Marcell Brüning (usually known as Marcell) seems to have come to England from Cloppenburg in Lower Saxony in about 1890 along with his brother Bernhard, assisting their older brother Conrad’s coal merchant’s business. The 1891 census found the family in Hampstead, and in 1901 Bernhard and Marcell were boarding in Kingston. In 1903 Marcell married Clara Mary Bagshawe, from a prominent Catholic family, whose Uncle Edward had recently retired as Bishop of Nottingham.

At this point Clara and Marcell were living a peripatetic life, living in Rochford, Essex, Newcastle, back to Rochford and then to New York, presumably for his coal dealing business. During these peregrinations, five sons were quickly born: Guy, Maurice, Roland, Peter and finally Clement in 1911.

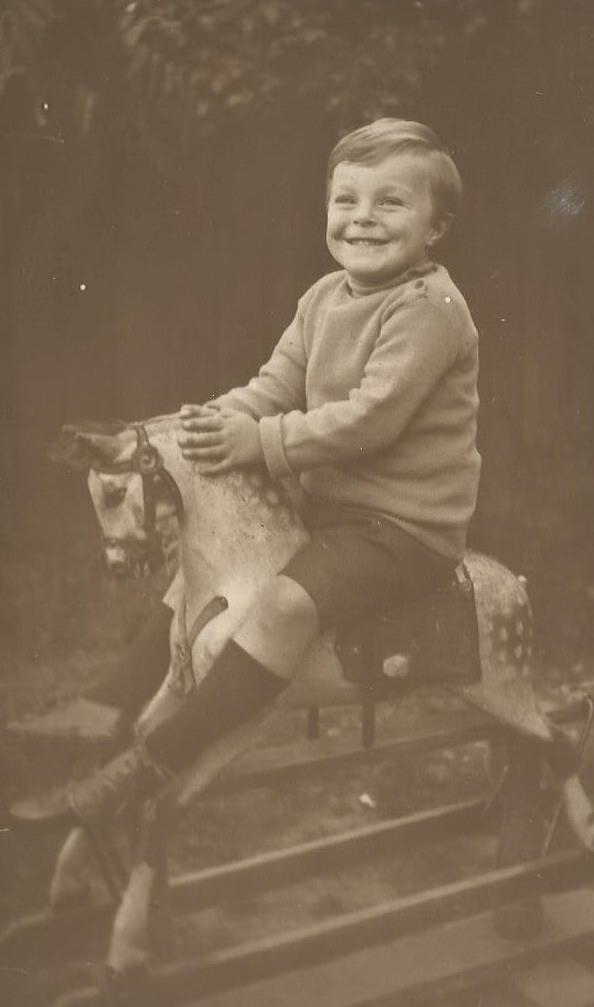

Here, in a family photograph, is a smiling young Clement on his rocking horse.

In 1921 most of the family were still abroad, but Clara was visiting her father in Chiswick (I used to have a pupil in the next road) while Guy, taking a break from his studies, was on holiday in Westcliff on Sea, near Southend and not far from his place of birth.

They must then have returned to settle in Ealing, the Queen of Suburbs, living in a large detached house just west of the Broadway. Clement was enrolled as a pupil at Ealing Priory (now St Benedict’s) School, which was where we found him in 1924.

Clement competed in both the London and British Boys’ Championships in 1925. In the latter event he shared third place in the top section, again drawing with Pratten in a game he should have won.

[Event “BCF-ch Boys U18 Final R3”]

[Date “1925.04.25”]

[White “Pratten, Wilfred Henry”]

[Black “Brüning, Clement Frederic”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. c3 d6 4. d4 Nf6 5. Bb5 Be7 6. Bg5 O-O 7. Bxc6 bxc6 8. Qd3 Nh5 9. h4 f5 10. Nbd2 d5 11. exd5 e4 12. Bxe7 Qxe7 13. Qe3 cxd5 14. g3 f4 15. gxf4 Nxf4 16. Rg1 Ba6 17. O-O-O Ne2+ 18. Kb1 Bd3+ 19. Ka1 Rab8 20. Rge1 Rxb2 21. Kxb2 Nxc3 22. Kxc3 Qa3+ 23. Nb3 Rxf3 24. Qxf3 exf3 25. Rxd3 Qxa2 26. Rxf3 Qa4 27. Kb2 h6 28. Ra1 Qc4 29. Rc3 1/2-1/2

John Saunders comments in BritBase:

Sources: Staffordshire Advertiser, 16 May 1925; BCM, May 1925, p216. The score of the game in BCM (from which the newspaper score may have been taken) gives the players as Bruning (White) and Pratten (Black) but the detailed description of the game on p214 makes it fairly certain that Pratten played White in the game: “In the last round Pratten very nearly had a shock. Opening with a Ponziani, which turned into a kind of Ruy Lopez after Bruning had played 3.., P-Q 3, he got a strong-looking game; but Bruning defended so well that the situation changed entirely to the holder’s disadvantage, and at last a sacrifice was obviously Black’s policy. Bruning saw this, but unfortunately sacrificed the wrong piece, and Pratten, by giving up his Queen, for adequate compensation, was able to extricate himself, and a draw resulted.” But we cannot be certain.

The computer informs me that White had an easy win in the final position, but no one seems to have realised this at the time. Insipid, as the Staffordshire Advertiser annotator calls it, it certainly wasn’t.

In 1926 he took part in the same two tournaments, but with less success, this time he performed poorly in his preliminary section of the British, but did manage to win his consolation event.

Perhaps this result was the reason why Clement decided to give up chess at this point.

In 1934, though, by which time the family, perhaps now less well off, had moved a mile to the west, to a semi-detached house in the less prestigious suburb of Hanwell, he was in the papers again, for a very different reason.

Over the next few years young Clement, clearly a young man with a gift for oratory, played an increasingly important role in Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, speaking at events around the South of England and writing letters to newspapers. His older brothers were apparently also Blackshirts, but didn’t play a prominent role.

(Another BUF member was aviation pioneer Alliott Verdon Roe, whose mother, Annie Sophia (Verdon) Roe, had been a regular competitor in the early years of the British Ladies’ Chess Championship.)

Clement is probably one of the young men in this photograph from a meeting in Eastbourne protesting against the Public Order Bill banning political uniforms: a reaction to the Battle of Cable Street.

A brief quote from the same source:

By 1937, and now the prospective parliamentary candidate for the Wood Green constituency, he had risen to the post of Propaganda Administrator for the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists, and was working closely with both Mosley and William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw).

He was often invited to speak at Rotary Clubs, for instance here in Cheshire.

He then moved to Bethnal Green, working for what was by then the British Union, and, when war was declared in 1939, was in Germany, apparently working for Welt-Dienst (World Service), an anti-Semitic broadcasting network.

Then something unexpected happened. He ended up in a concentration camp, where he was murdered by the Nazis on 17 August 1942. What had happened? We know he was being investigated by MI5. Perhaps he’d changed his opinion and fallen foul of the Nazis, or maybe he’d been recruited as a double agent. Nobody knows, or if they do they’re not telling. A very sad and mysterious end for the cute, chubby-cheeked smiling lad on the rocking horse, for the young perpetrator of dashing but unsound attacks in his three years of participation in boys’ chess tournaments.

Two contrasting stories, then, the brilliant mathematician and philosopher whose name was Black, and his rival whose shirt was black, and whose premature endgame resulted in tragedy.

But what of the other eight pioneers of London Boys’ Chess? Their lives, as far as I can tell, took rather more conventional courses.

The tournament winner, with a 100% score, was J Allcock of Coopers’ School, now in Upminster, but then in Bow Road, East London. I believe this was Jack Adams Allcock (1906-1969), who lived very close to the school. He was clearly a promising player, but seems to have played little chess on leaving school. We can pick him up playing for London University in 1928, and in the London League for North London in 1933. His father ran an off licence in Bow, later becoming the landlord of the Duke of York in Hackney, and it seems that Jack and his wife Eliza helped him running the pub. In spite of Jack’s education the family were never well off, both Jack and Eliza leaving very little money. I can’t find any immediate connection with the strong City of London player James Frederick Allcock.

In second place, on 6½/9, was Stanley Thomas Henry Goodwin, born in 1906, and, like Max Black, a pupil at Dame Alice Owen’s School. Also from Hackney, Stanley’s father Vincent was a Post Office sorter. He married in 1932, and the 1939 Register found him living in North London and working as a brewery clerk He served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in World War 2, and, it seems later emigrated to Australia where he died in Perth, but I don’t have a death date. I have no further record of any chess activity after this tournament.

Percy Geoffrey Husbands (1906-1987) of Regent Street Polytechnic scored 5/9 for fourth place. Percy lived in Ealing: his father Basil was working as a furniture dealer in 1911, but by 1921 he was a house furnisher and decorator, no longer employing servants. In 1934 Husbands became a husband, marrying Lucy Sophia Eavis, whose family owned (and still own) Worthy Farm near Glastonbury. Michael Eavis, the founder of the Glastonbury Festival, is the son of Lucy’s half-brother Joseph Eavis. By 1939 Percy was living in Uckfield, Sussex, working as an Insurance Clerk. His chess career continued in the 1924 British Boys’ Championship and the minor section of the London tournament in 1924-25, but after this event he seemed to stop playing: perhaps work, as it often does, got in the way.

Being confronted by J Smith is a genealogist’s nightmare, and that’s who we have on 4/9. We do know, though, that he was John B Smith of Sir Walter St John School in Battersea, and that he also played in the following year’s tournament. The most likely candidate is John Bryan Smith, born in 1908, the son of a plumber from Wandsworth. He spent much of the 1930s travelling 1st class to and from West Africa, described first as an Assistant and then as a Merchant’s Agent before disappearing from view.

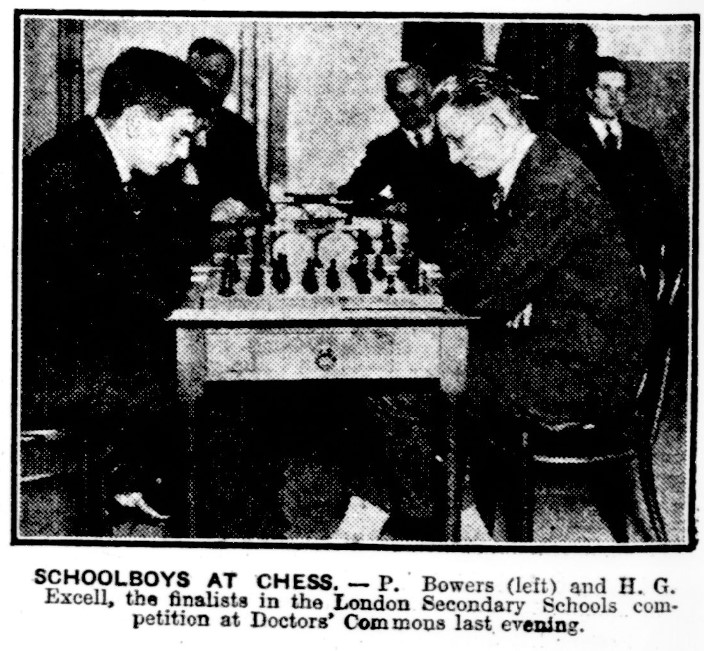

On 3½/9 we find Hugh George Excell (1907-1993) from North London Chess Club. Hugh was the son of an Insurance Claims Inspector from Hackney. He signed up for the Royal Artillery in June 1939, but in September that year was living with his fiancée in Suffolk. Hugh continued playing competitive chess occasionally until at least 1932, including this tournament the following year, and, most notably, one of the first class sections in the 1929 Ramsgate Easter Congress. In the later 1930s he took up correspondence chess, but his chess career seems to have ended with the outbreak of the Second World War.

Here he is, playing in the London Secondary Schools competition (a separate event) in 1925.

His opponent in this game was Philip Ernest Bowers (1908-1999), who scored 3/9 in the inaugural London Boys’ Championship. Philip was the son of a Police Constable, originally from Norfolk, but who was living in Chelsea by 1921. He was a pupil at Westminster City School, and would also compete in this tournament for two more years. He returned to chess in 1935, by which time he had moved to Birmingham, and rose rapidly through the ranks to become one of his club’s leading players. By 1940 chess activity there was curtailed by the war, and it seems that, like many others, Philip stopped playing at this point. Like many chess players, he spent his adult life teaching maths.

Known as ‘Bill’ rather than Philip, here he is pictured later in life from an online family tree.

Half a point below him, and half a point above Clement Brüning in 9th place was Jack Liebster (1907-1996), the son of a Russian born GP from Stoke Newington. Both his parents were Jewish, but his mother was born in Stepney: Jack was the youngest of their five children. Chess must have been played in the family: his father is recorded as submitting correct solutions to problems in the London Daily Chronicle in 1901, but this was to be, as far as I can tell, his only experience of competitive chess. In the 1939 Register Jack was described as a Traveller, and also as an ambulance driver. He married a chemist’s daughter in 1941, and they moved to Dunstable, where they had two children and played a significant role in the local Jewish community.

That leaves one other player, variously recorded as JS Lauder or JS Lander, whose score of 3½ left him level with Hugh Excell. I can’t find anyone with that name in the right place at the right time, but I did find Joseph John Lauder (1906-1999), the son of a Scottish born Police Inspector based at Wimbledon Police Station. He was certainly a chess player, and, more importantly, a much respected chess administrator for many years. Joseph (Harry to his friends, Mr Lauder to me) was secretary of both the Surrey County Chess Association and the Southern Counties Chess Union for many years and later, in the 1970s, the SCCU Bulletin Editor. I used to visit his home in Wimbledon every year to collect our club copies of the SCCU Grading List. Quite rightly, the chess players of Surrey now compete for a trophy named in his honour. There’s no way of knowing for certain, but I do hope it was him.

There are no more pre-war chess references, but we can pick Mr Lauder up in the 1939 Register, where he was employed as a Bank Clerk and living in the next road to where he was in the 70s. The first post-war chess record I can find for him is in 1947, playing for his local club. For some years he played regular club and county chess, also enjoying competing at Bognor Regis every year up to 1962. He was a decent, above average club strength player, but it was as an administrator that he deserves to be – and still is – remembered.

There’s much more to be written about the teenage boys who played tournament chess in the 1920s. At some point I’ll introduce you to some of the other LBCC players, and perhaps some of the other competitors in the British Boys’ Championship during that period.

Sources and Acknowledgements

ancestry.co.uk (Black, Brüning and Bowers family trees)

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archives

Wikipedia

Google Books (search for Max Black and Clement Brüning)

MacTutor

British Chess News

chessgames.com

ChessBase 18/Stockfish 17

Surrey County Chess Association and Southern Counties Chess Union archives/websites

Various other sources mentioned above

Leave a reply to Minor Pieces 86: London Boys Chess Championships (2) – Minor Pieces Cancel reply