Last time I considered Charles Dealtry Locock’s tournament and match play in the 1880s and 1890s, at which point he gave up competitive chess.

But it was far from the end of his chess career. Alongside his chess playing he had a parallel career as a chess problemist.

In The Chess Bouquet (1897) he was given the opportunity to say something about how he started to take an interest in the problem art.

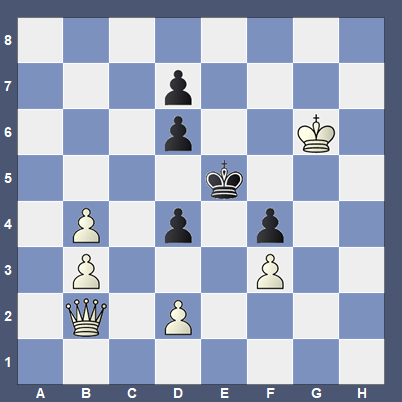

Here’s that first problem. The solutions to all problems are at the end of this article.

18-02-1882

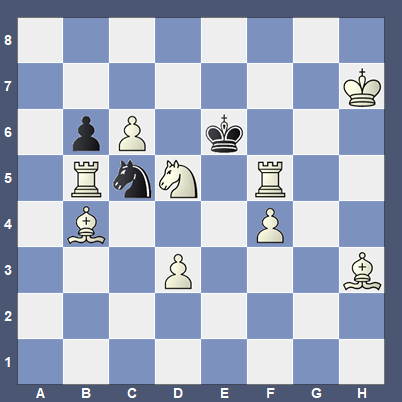

Here’s another early problem.

But these represented just an early dalliance in the problem world. Concentrating on his studies and over the board play, he took a break from composition, only returning in 1890.

This miniature had probably first been published in Tinsley’s Magazine a few months earlier.

He published a few more problems in 1891, gradually increasing his production over the next few years as he stopped playing tournament chess.

Most of the problems were mates in 2 or 3 moves (quite a few of them, sadly, cooked, which suggests, as does his play, a certain carelessness), but also a few selfmates. By now he had a column in Knowledge, which ran from 1891 to 1904, which provided an outlet for some of his compositions.

While some of them were complex, he also published a lot of simpler problems suitable for casual readers, often employing perennially popular themes such as queen moves to corners, star flights and switchbacks.

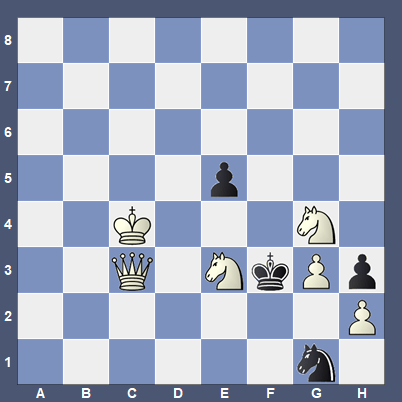

In 1892 Locock made a brief excursion into the world of endgame studies, with this early example of Co-ordinate Squares.

You’ll see Locock was living in Kingston at the time, but by the September he’d moved down the road to Putney Heath.

I haven’t been able to find anything further, either in the 1892 or 1893 BCM, perhaps unsurprisingly, since the position is drawn, regardless of whose move it is. If it’s Black’s move, though, the only drawing move is 1… Kg7.

If, however, you start with the white king on a1 instead, then you have an excellent study. It was published with this correction in the Deutsche Schachzeitung in October 1914.

White wants to meet Kf6 with Kd4, and therefore also wants to meet Kg5 with Ke3. There’s only one route to get there.

July 1892 (corrected)

In the 1893 Christmas Special issue of the British Chess Magazine, Locock offered a puzzle involving retroanalysis.

Here’s the published solution. I’ll leave to experts in this field to comment.

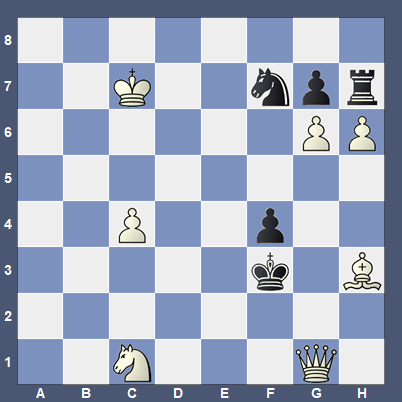

His problems didn’t win a lot of prizes, but this Mate in 3 from 1896 was a first prize winner.

In The Chess Bouquet Locock discussed his ‘decidedly heterodox’ views on chess problems.

He concluded like this.

This is one of the problems he composed for The Chess Bouquet.

Although he retired from competitive chess in 1899, Locock certainly didn’t retire from composition, although he was increasingly drawn to 3-movers rather than 2-movers. Some of them are pretty complex, but this one is rather sweet and certainly accessible to the casual solver.

This more complex mate in 3 was a 1st prize winner in 1933.

Now let me take you back to 1909. On April 1 (note the date), Locock wrote to the editor of the BCM:

A sui-mate is what we’d now call a selfmate. Black compels a reluctant White to deliver checkmate.

For those of you who aren’t bilingual, here’s the game.

1. c4 e5 2. Nc3 Ke7 3. Nf3 Kd6 4. Nd4 Qh4 5. e4 Ne7 6. Ke2 Qxe4+

Locock would maintain an interest in these tasks, known as Synthetic Games, throughout the rest of his long life. In 1944 he published a whole host of them in the BCM. Note that, unlike in Proof Games, there are often multiple solutions.

You might like to try a couple here.

Synthetic Game 1: White opens 1. Nc3 and delivers a pure mate (there’s only one reason why the king cannot move to any adjacent square) with the queen’s rook on the 5th move. (British Chess Magazine May 1944)

Synthetic Game 2: Black mates on move 5 by promotion to a knight (this is also a pure mate). (Manchester Weekly Times 28 Dec 1912)

If you’re interested in synthetic games you’ll want to read this comprehensive and authoritative paper written by George Jelliss.

There, then, you have the problem career of Charles Dealtry Locock, who, as well as being a very strong player during the 1880s and 1890s, held an important and, you might say, unique place in the chess problem world for more than 60 years. If you’d like to see more of his problems, check out the links to YACPDB and MESON at the foot of this article.

But there was much more to Locock’s chess life than playing and composing, as you’ll find out next time. Be sure not to miss it.

Solutions to Problems, Study and Synthetic Games:

Problem 1.

1. Qa1 d5 (1… Ke6 2. Qe1+ Kd5 3. Qe4#) (1… Kd5 2. Qa8+ Ke6 (2… Ke5 3. Qe4#) 3. Qe4#) 2. Qa6 d6 (2… d3 3. Qf6#) 3. Qe2#

Problem 2

1. Bg2 Kxf5 (1… Nxd3 2. Rf6# (2. Nc7#)) (1… Ne4 2. Nc7#) (1… Nd7 2. Nc7#) (1… Kd6 2. Rf6#) 2. Bh3

Problem 3.

1. Nc4 Kd5 (1… Kf4 2. Qe3#) (1… d5 2. Qe3#) (1… f4 2. Nxd6#) 2. Nd2#

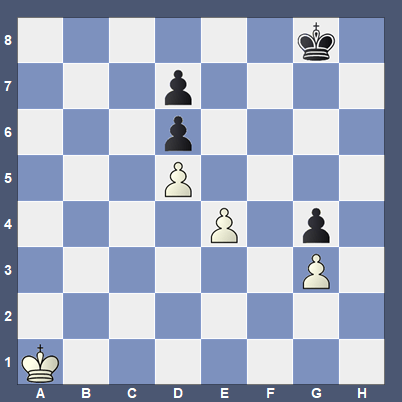

Problem 4.

1. Qa1 Ke4 (1… Ne2 2. Qh1#) (1… Ke2 2. Qd1#) (1… e4 2. Qf1#) 2. Qa8#

Study.

1. Kb1! (1. Kb2? Kh8 ! 2. Kc3 Kg7 3. Kd3 Kg6) (1. Ka2? Kg7 2. Kb2 Kh8) 1… Kg7 2. Kc1! Kg6 3. Kd1! Kg5 4. Kc2 Kh5 5. Kc3 Kg5 6. Kc4 Kg6 (6… Kf6 7. Kd4) 7. Kd3 Kg5 (7… Kg7 8. Ke3 Kg6 9. Kf4) 8. Ke3 Kf6 9. Kd4 1-0

Problem 5.

1. Nb3 {Threat: 2. Bg4+ Ke4 3. Qd4#} Ke2 (1… Ke4 2. Nc5+ Ke5 (2… Kf3 3. Bg4#) 3. Qa1#) (1… Nxh6 2. Qe1 Nf5 3. Nd2#) (1… gxh6 2. Bg4+ Ke4 3. Qd4#) (1… Ng5 2. Bg4+ Ke4 3. Qd4#) (1… Ne5 2. Nd4+ Ke4 3. Bf5#) 2. Bf1+ Kf3 (2… Ke1 3. Bd3#) (2… Kd1 3. Bd3#) 3. Nd2#

Problem 6.

1. Kd1 Kd5 (1… Re1+ 2. Rxe1#) (1… Bxg6 2. Qc5#) (1… Bg1 2. Rh5#) (1… Rf4 2. Qc5#) (1… Bf4 2. Qc5#) (1… Rc4 2. Nxf7#) (1… Rd4+ 2. cxd4#) 2. Qd4# 1-0

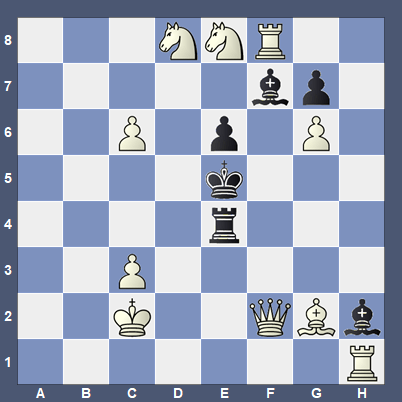

Problem 7.

1. Bh1 b6 (1… bxc6 2. Qa8 cxb5 3. Qf3#) 2. Kg2 Ke4 3. Kg3#

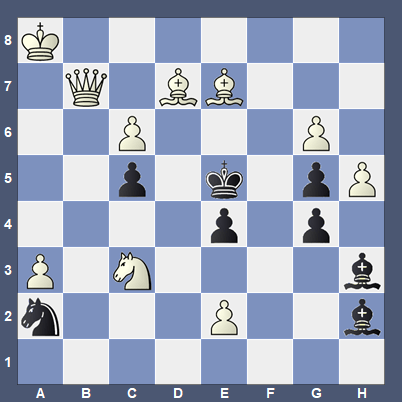

Problem 8.

1. Qb2 {Threat: Qd2 and Qd6#} Kf4 (1… Kd4 2. Qd2+ Kc4 (2… Ke5 3. Nd5) 3. Be6#) (1… g3 2. Bf6+ Kxf6 (2… Kf4 3. Nd5#) (2… Kd6 3. Qb8#) 3. Nd5#) (1… e3 2. Bf6+ Kxf6 (2… Kf4 3. Qb8#) (2… Kd6 3. Qb8#) 3. Nd5#) (1… Nc1 2. Nd1+ Kd5 (2… Kf4 3. Qb8#) 3. Ne3#) (1… Nxc3 2. Qxc3+ Kf4 3. Bd6#) (1… Nb4 2. Nd1+ Kd5 (2… Kf4 3. Bd6#) 3. Ne3#) (1… Bf4 2. Bf6+ Kxf6 (2… Kd6 3. Qb8#) 3. Nd5#) (1… Bg1 2. Qd2 Bd4 3. Qxg5#) 2. Bd6+ Ke3 3. Nd1#

Synthetic Game 1.

1. Nc3 e5 2. a3 Bxa3 3. Ne4 Bf8 4. Ra5 Ke7 5.Rxe5#

Synthetic Game 2.

1. b3 e5 2. d3 e4 3. Kd2 exd3 4. Kc3 dxe2 5. Kb2 exd1=N#

Sources and Acknowledgements

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

The Chess Bouquet (FR Gittins: here)

British Chess Magazine (various issues)

Internet Archive (here)

Chess Archaeology (here)

The Problemist

Yet Another Chess Problem Database (here)

MESON Chess Problem Database (here)

Synthetic Games (George Jelliss: here)

Leave a reply to Minor Pieces 76: Charles Dealtry Locock (3) – Minor Pieces Cancel reply