You know the story, of course. It comes from Shaw’s play Pygmalion, but was made famous by the Lerner & Loewe musical My Fair Lady (by the way, I can strongly recommend John Wilson’s recent recording).

The story concerned Eliza Doolittle, a cockney flower seller (like Lonnie Donegan and Leonard Barden, her old man was a dustman), who was taught by Professor Henry Higgins how to pass herself off as a lady.

A very similar story took place in real life a few decades earlier, also featuring a girl named Eliza, also with a euphonious surname. In her case, though, her name was romantic rather than indolent: Eliza Truelove.

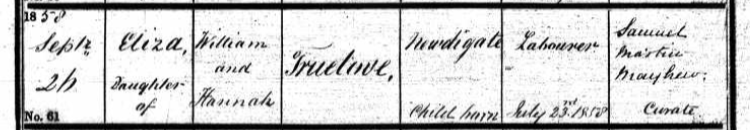

Unlike Miss Doolittle, Miss Truelove was a country girl. She was born on 23 July 1858, in the Surrey village of Newdigate, situated to the west of what is now Gatwick Airport.

We can find the family in the 1861 census: William, an agricultural labourer, his wife Hannah and their children Mary, William, Thomas, Ann, Eliza and baby Caroline.

Hannah died in 1869, and, by 1871, William had moved a few miles south to Rusper, in Sussex. He was still an agricultural labourer, as were William junior and Thomas. Eliza and Caroline had been joined by their youngest brother, John, while Mary and Ann had both left home to work in service.

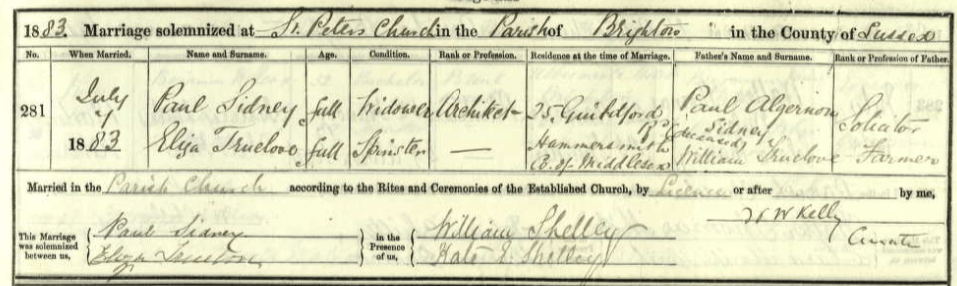

I haven’t yet been able to locate Eliza in the 1881 census, but we can find her in Brighton, in 1883, where she married a widower, Paul Sidney.

Let’s stop for a moment and look at Paul Sidney’s story.

He was born in London to a wealthy family in 1830, so he was a lot older than Eliza. Here he’s described as an architect, but was also a property developer. His first marriage, in 1852 to Mary Ann Gill, took place just down the road from me, in Richmond. He was left a widower when she died, perhaps in London in 1878.

It’s not known at the moment where and how Paul and Eliza met, or what they were doing in 1881: perhaps they were on holiday abroad.

Paul was a chess enthusiast and taught his wife to play. A later interview told the story:

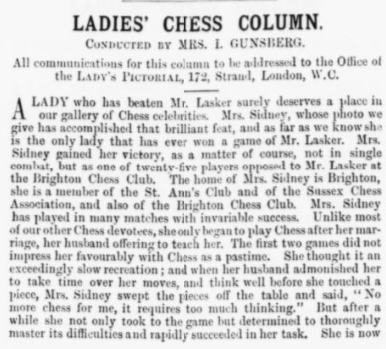

… she only began to play Chess after her marriage [in 1883], her husband offering to teach her. The first two games did not impress her favourably with Chess as a pastime. She thought it an exceedingly slow recreation; and when her husband admonished her to take time over her moves, and think well before she touched a piece, Mrs. Sidney swept the pieces off the table and said, “No more chess for me, it requires too much thinking.” But after a while she not only took to the game but determined to thoroughly master its difficulties and rapidly succeeded in her task

By 1888 we can find them both in Brighton Chess Club: Paul was in Class 7 of the Handicap Tournament, and his wife in Class 5 of the Ladies’ Handicap Tournament: in both cases the lowest of the low.

The 1891 census recorded the Sidneys as living in an apartment at 17 St Aubyn’s, Hove. Paul was a retired architect and Eliza was now giving her name as Ellen. They employed a domestic servant, also named Ellen.

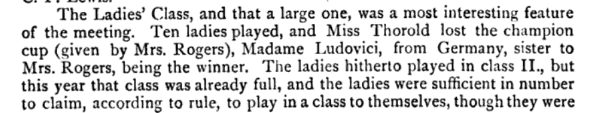

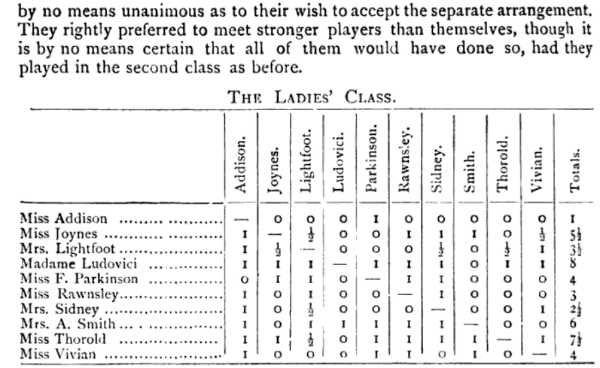

The 1892 Counties Chess Association meeting took place in Brighton, featuring a Ladies’ Tournament with ten entries. Mrs Sidney took part, but without much success.

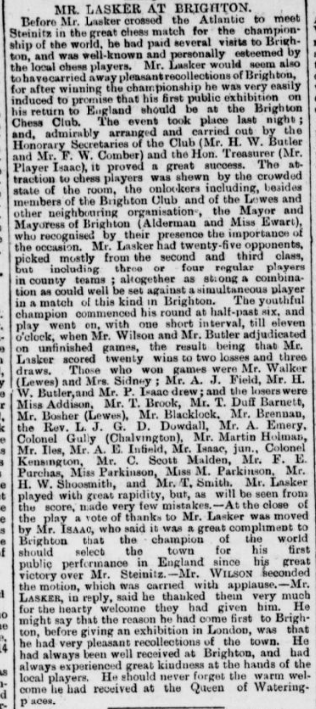

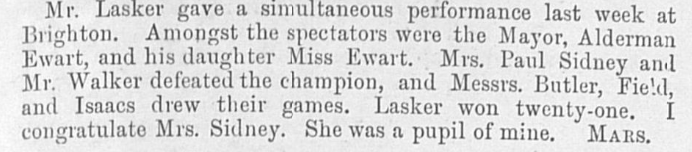

Mrs Sidney’s determination to master the difficulties of chess led to lessons with Rev George Alcock MacDonell. When Lasker was in town in 1894 it was clear that they’d paid off.

Her teacher was delighted to be able to congratulate her.

Unfortunately, the game hasn’t survived, but her feat earned her an article in the Lady’s Pictorial the following year.

In 1895 she took part in the Major section of the Ladies’ Tournament at Hastings.

07 September 1895

She was the only player to defeat Rita Fox, about whom more in a future Minor Piece, and had seemingly made considerable progress since her previous tournament outing.

However, she lost a piece in the opening against Kate Finn.

[Event “Hastings Ladies’ Major Tournament”]

[Date “1895.08.27”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Finn, Kate Belinda”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. e5 Nfd7 5. f4 c5 6. dxc5 Bxc5 7. Nf3 Qb6 8. Qe2 a6 9. Na4 Qa5+ 10. Nc3 d4 11. Nxd4 Bxd4 {…} 0-1 (Source: Lady’s Pictorial 05 October 1895)

Over the 1895-96 holiday period she visited Hastings, playing an informal match against Miss Colborne, which she lost by two games to three. (I believe this is Hilda, from a chess playing family, rather than her artist sister Vera.)

In this game Hilda was doing well until playing a totally unsound piece sacrifice.

[Event “Match: Hastings”]

[Date “1897.01.??”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Colborne, Hilda”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 b6 2. d4 Bb7 3. Bd3 e6 4. Ne2 d6 5. Nbc3 Nf6 6. f3 Nbd7 7. Nf4 e5 8. dxe5 dxe5 9. Nfe2 Bd6 10. Bg5 h6 11. Bh4 Qe7 12. Bf2 Nh5 13. Ng3 Nf4 14. O-O g6 15. Nge2 Qg5 16. Nxf4 exf4 17. Bb5 O-O-O 18. Qe2 h5 19. Ba6 h4 20. h3 Bc5 21. Bxb7+ Kxb7 22. Rad1 c6 23. a3 Rhe8 24. Qe1 Ne5 25. Bxc5 Nxf3+ 26. Rxf3 Qxc5+ 27. Kh1 b5 28. Rfd3 Rxd3 29. Rxd3 f5 30. Qd1 fxe4 31. Rd7+ Ka6 32. a4 Qc4 33. axb5+ cxb5 34. Qa1+ Kb6 35. Qxa7+ {Source: Lady’s Pictorial 16-01-1897} 1-0

The roles were reversed in this game: Helen was doing well until allowing a neat tactical shot.

[Event “Match: Hastings”]

[Date “1897.01.??”]

[White “Colborne, Hilda”]

[Black “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bg5 Be7 5. e5 Nfd7 6. Bxe7 Qxe7 7. Bd3 c5 8. Bb5 a6 9. Bxd7+ Bxd7 10. Qg4 O-O 11. Nge2 Nc6 12. Qf4 f6 13. exf6 Rxf6 14. Qd2 cxd4 15. Nxd4 Raf8 16. Rf1 Ne5 17. f3 Ng4 18. O-O-O Ne5 19. Rfe1 Nc4 20. Nxd5 Nxd2 21. Nxe7+ Kh8 22. Rxd2 Re8 23. Nd5 exd5 24. Rxe8+ Bxe8 25. Re2 Bf7 26. Re7 b5 27. Ra7 h6 28. Nb3 Bg6 29. Nc5 Rc6 30. Rxa6 Rxa6 31. Nxa6 {Source: Lady’s Pictorial 16 January 1897} 1-0

As a result of her growing reputation, she was invited to take part in the London International Ladies’ Tournament in 1897.

There she is, seated on the right of the front row, looking rather imperious: not in the least like the daughter of a humble farm labourer. One wonders if, like Eliza Doolittle, she had elocution as well as chess lessons.

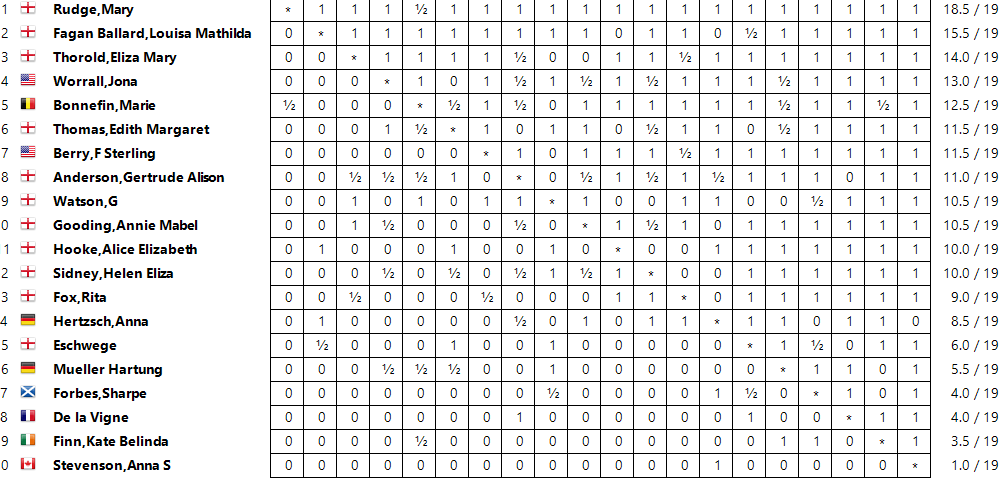

You’ll see from the crosstable that she performed respectably, scoring 10/19, just half a point below Annie Mabel Gooding and level with Alice Elizabeth Hooke.

Three of her games have survived.

In the first round the eventual bottom-marker gave her no problem – and a couple of pieces.

[Event “London International Ladies’ Tournament R1”]

[Date “1897.06.23”]

[White “Stevenson, Anna S”]

[Black “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 c5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. Nf3 e6 4. d3 d6 5. d4 cxd4 6. Nxd4 Nf6 7. Be2 Qb6 8. g3 Nxd4 9. Be3 e5 10. O-O Nxe2+ 11. Qxe2 Qc6 12. Qd3 Be7 13. a4 b6 14. b4 Bb7 15. b5 Qc7 16. f3 Rc8 17. Ra3 O-O 18. Qd2 h6 19. h3 Rfd8 20. Rd1 d5 21. Qe1 Bxa3 {…} 0-1

In the second round, a pre-Nimzo example of a Nimzo-Indian Defence, she herself was guilty of hanging a piece in the opening against the eventual runner-up.

[Event “London International Ladies’ Tournament R2”]

[Date “1897.06.23”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Fagan, Louisa Mathilda”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. d4 e6 2. c4 Bb4+ 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. a3 Bxc3+ 5. bxc3 c6 6. Bg5 Qa5 7. Qd3 Qxg5 8. Nf3 Qf5 9. Qd2 Ne4 10. Qb2 d5 11. cxd5 exd5 12. e3 O-O 13. Bd3 Re8 14. O-O Nd7 15. Rae1 Nb6 16. Nd2 Qf6 17. Nxe4 dxe4 18. Bc2 Qh6 19. Bd1 Nc4 20. Qc1 Qd6 21. a4 Qa3 22. Qc2 Qb2 23. Qb3 Qxb3 24. Bxb3 Nd2 0-1

These games, it must be admitted, don’t give a very positive view of standards in women’s chess at the time.

Her other surviving game, where she took her revenge against Kate Finn, was a much more creditable effort.

[Event “London International Ladies’ Tournament R8”]

[Date “1897.06.26”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Finn, Kate Belinda”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Nf3 Be7 5. e3 c5 6. Bd3 dxc4 7. Bxc4 Nc6 8. O-O b6 9. b3 O-O 10. Bb2 Bb7 11. Qe2 Rc8 12. Rad1 Qc7 13. dxc5 Bxc5 14. Nb5 Qe7 15. a3 Rfd8 16. b4 Bd6 17. Nxd6 Rxd6 18. Rxd6 Qxd6 19. Rd1 Qe7 20. Ba6 Bxa6 21. Qxa6 Rd8 22. Rxd8+ Qxd8 23. h3 h6 24. Bxf6 Qxf6 25. Qc8+ Nd8 26. Nd4 e5 27. Nf3 Kh7 28. Qc7 a5 29. bxa5 bxa5 30. Qxa5 Nc6 31. Qb5 Na7 32. Qxe5 1-0

Black chose the wrong recapture on move 24, and ended up losing a couple of pawns.

In 1898 she was involved with the foundation of Hove Chess Club, noted, according to Brian Denman (Brighton Chess) for its hospitality and refreshments. “Players could choose between tea and coffee, and the lady members also prepared toasted tea cakes, muffins, sandwiches and a succulent array of cream cakes and sponges.” She presented a trophy for the club championship which bore her name. This club continued until the outbreak of World War 2, and Mrs Sidney won her own trophy on six occasions between 1922 and 1934.

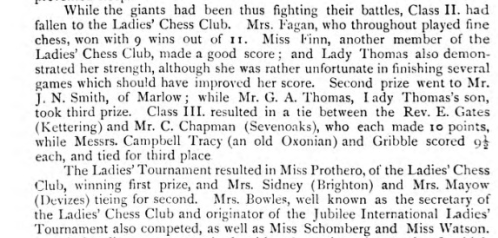

That autumn, Mrs Sidney travelled to Salisbury for the Southern Counties Chess Union congress, taking part in the Ladies’ Tournament. (Note that ‘Miss Watson’ should read ‘Mrs Rumboll’.)

This was a great period for women’s chess in England, with leading players such as Mrs Fagan playing successfully in open competition. Sadly, Miss Prothero, the winner of the Ladies’ Tournament, died just a year later.

In the 1901 census, Mrs Sidney gave her name, neither as Eliza or Ellen, but as Elizabeth, also taking a few years off her age, claiming to be 38 rather than 42. Her niece Ellen Louisa Truelove was also in residence, perhaps helping with the housework.

Two of her games from 1902 have survived. This was from the play-off of the Sussex Ladies’ Championship, which Mrs Sidney won on many occasions. Mrs Herring would later win the British Ladies’ Championship on two occasions: in 1906 and 1907.

[Event “Sussex Ladies Championship play-off”]

[Date “1902.??.??”]

[White “Herring, Frances Dunn”]

[Black “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 c5 2. Nc3 g6 3. Nf3 Bg7 4. d3 d6 5. Be2 Nc6 6. Rb1 a5 7. a3 h6 8. Bd2 Nd4 9. Nd5 Nxe2 10. Qxe2 Nf6 11. Bc3 Nxd5 12. Bxg7 Nf4 13. Qd2 Nxg2+ 14. Kf1 Rh7 15. Bxh6 Bh3 16. Ke2 e5 17. Rbg1 b5 18. Be3 f6 19. Ne1 Nh4 20. Rg3 Be6 21. f4 exf4 22. Bxf4 g5 23. Be3 Qc8 24. Rhg1 Ng6 25. Kd1 Ne5 26. Kc1 Qd7 27. Rf1 Ke7 28. Bg1 b4 29. c4 bxa3 30. bxa3 Qa4 31. Qc3 Rb8 32. Nc2 Rb3 33. Qd2 Rh8 34. Kd1 Rxa3 35. Ke2 Ra2 36. Rc1 Rb8 37. h3 Rbb2 38. Kd1 Qb3 39. Re3 Qa4 40. Bh2 Nc6 41. Qc3 Nd4 42. e5 dxe5 43. Bxe5 fxe5 44. Rxe5 Nxc2 45. Rxc2 Rxc2 {Sources: Hastings and St Leonards Weekly Mail and Times of 31.5.1902, and the Sussex Chess Association Annual Report for 1902.} 0-1

In this game, Mrs Sidney displayed a fondness for modern openings and strong attacking skills after White’s mistaken 29. c4 (29. d4 would have been much better).

She lost this game, though, from a match between the ladies of Brighton and Hastings. Her opponent came from a chess playing family. One of her brothers was Herbert Edward Dobell, whom I ought to feature at some point, and their jeweller father Ebenezer also played.

[Event “Hastings Ladies v Brighton Ladies B1”]

[Date “1902.12.11”]

[White “Stevens, Emily Margaret”]

[Black “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 c5 2. d4 cxd4 3. Qxd4 Nc6 4. Qd1 e5 5. Nf3 Nf6 6. Nc3 Bb4 7. Bd3 d6 8. Bg5 O-O 9. O-O Bg4 10. Nd5 Nd4 11. Nxb4 h6 12. Bh4 g5 13. Bg3 a5 14. Nd5 Nxd5 15. exd5 Qf6 16. Be4 Qe7 17. c3 Nb5 18. h3 Bh5 19. Qd3 Nc7 20. Bh2 f6 21. Bg6 Bxf3 22. Qxf3 Qg7 23. Bf5 b6 24. Rfe1 Na6 25. Qh5 Ra7 26. Re4 Nc7 27. Rd1 Na6 28. Rg4 Nc7 29. Rd3 Na6 30. Rdg3 Nc7 31. Rh4 Kh8 32. Qxh6+ Kg8 33. Qxg7+ Kxg7 34. Rh5 Nxd5 35. Rh7+ Kg8 36. Rxa7 {Source: Hastings and St Leonards Observer of 20.12.1902. Played at Brighton.} 1-0

If she’d only read Chess Heroes: Openings, Mrs Sidney would have played 9… Bxc3 rather than allowing the decisive Nd5.

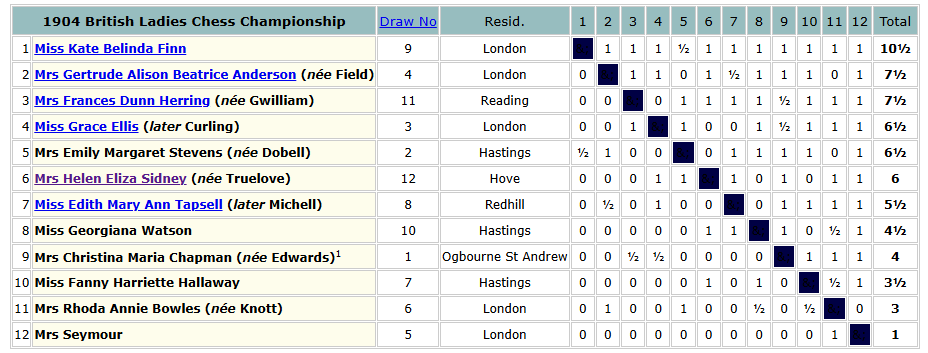

1904 saw the first British Chess Championships, held in Hastings, and Mrs Sidney was invited to take part.

She lost this game against Mrs Anderson.

[Event “British Ladies Championship: Hastings R6”]

[Date “1904.08.29”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Anderson, Gertrude Alison Beatrice”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 c6 4. Nf3 Nf6 5. Bg5 Be7 6. e3 b6 7. Rc1 a5 8. a4 Ba6 9. Ne5 O-O 10. Bd3 dxc4 11. Nxc4 Bxc4 12. Bxc4 Nd5 13. Bxe7 Qxe7 14. e4 Nxc3 15. bxc3 Nd7 16. O-O Rad8 17. f4 Nf6 18. e5 Nd5 19. f5 Ne3 20. Qb3 Nxf1 21. Rxf1 exf5 22. Rxf5 Rb8 23. g3 Qe8 24. h4 b5 25. axb5 cxb5 26. Bd5 b4 27. e6 fxe6 28. Bxe6+ Kh8 29. Rxf8+ Qxf8 30. c4 a4 31. Qxa4 Qd6 32. Bd5 Qxg3+ {Source: Birmingham News 1.10.1904.} 0-1

I wonder whether she saw that her 19th move allowed a knight fork. It was, in fact, an excellent choice, because 20. f6 was winning, but, without Stockfish to consult she missed it, losing the exchange.

At the same time she was engaged in a correpondence match between Sussex and Suffolk, where she was pitted against a Roman Catholic clergyman.

[Event “Suffolk v Sussex corr. match B23”]

[Date “1904.??.??”]

[White “Peacock, Augustine Peter”]

[Black “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. f4 d5 3. exd5 e4 4. Bc4 Nf6 5. Nc3 Bb4 6. Nge2 c6 7. dxc6 Nxc6 8. a3 Qa5 9. d4 exd3 10. Bxd3 O-O 11. Be3 Bxc3+ 12. Nxc3 Re8 13. Qd2 Qb6 14. Ne4 Nxe4 15. Bxb6 Nxd2+ 16. Kxd2 axb6 {‘And Black won with the extra piece.’ Source: West Sussex Gazette 9.2.1905.} 0-1

She entered the 1905 British Ladies Championship in Southport, but retired after suffering defeats in her first two games, presumably for health reasons. She didn’t take part the following year: there was an indication in the local press that she had taken a short break from chess.

But she was back again in London in 1907, scoring 7/11 to finish in fourth place, just ahead of Annie Gooding, with Alice Hooke trailing.

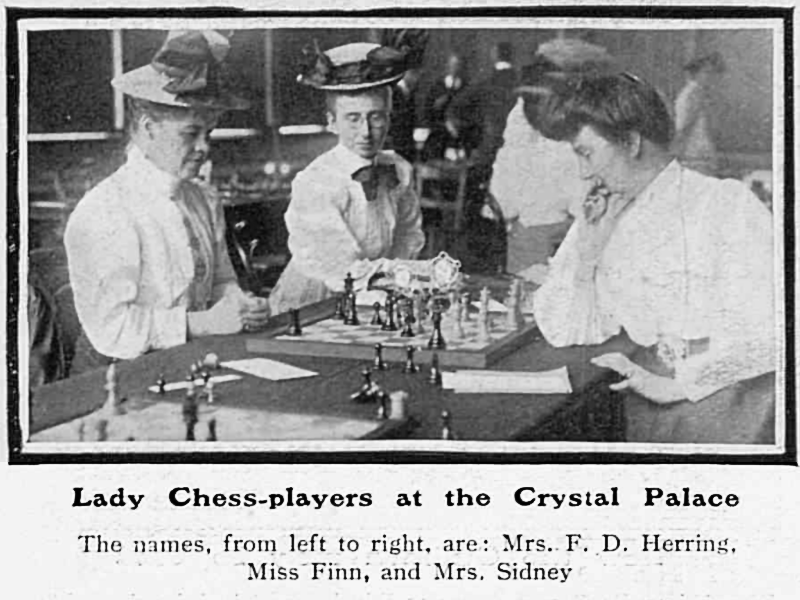

Here she is, playing White against Frances Herring, with Kate Finn, there as a spectator, looking on.

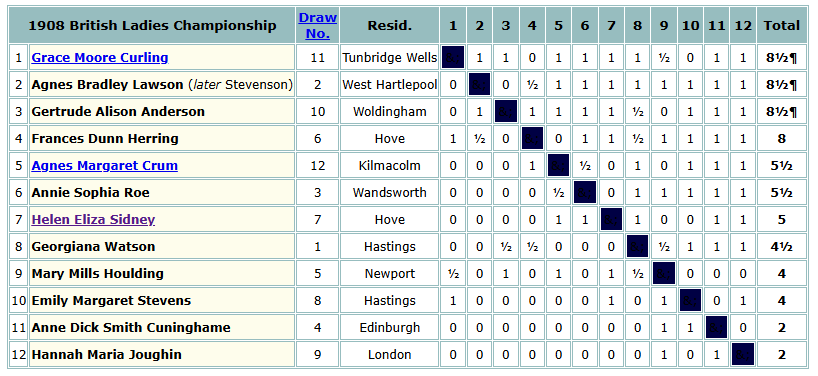

She was less successful in Tunbridge Wells in 1908, by which time she had played 35 decisive games in the British Ladies Championship, suggesting an aggressive and uncompromising playing style.

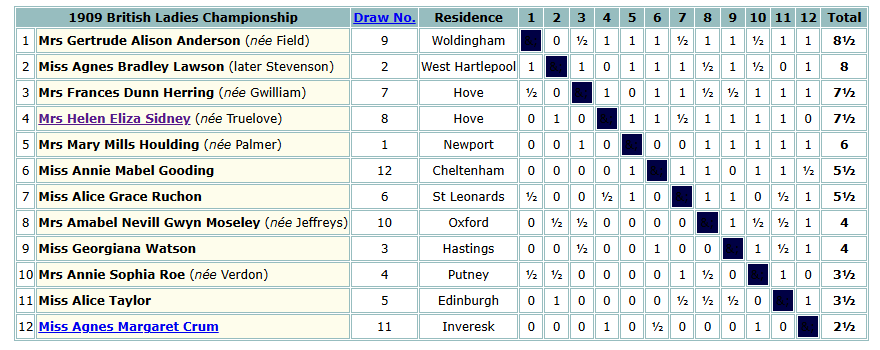

Scarborough in 1909 saw her best result yet, sharing third place with her Hove neighbour Frances Herring. If she’d managed to beat the bottom placed Miss Crum she’d have shared first place. She did finally manage to draw a game here.

Here’s her win against the second placed Agnes Lawson.

[Event “British Ladies Championship: Scarborough R8”]

[Date “1909.08.17”]

[White “Sidney, Helen Eliza”]

[Black “Lawson, Agnes Bradley”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. d4 d5 2. Nf3 Bf5 3. c4 e6 4. Nc3 Nf6 5. Nh4 Be4 6. f3 Nh5 7. g3 Bg6 8. Nxg6 hxg6 9. g4 Qh4+ 10. Kd2 Ng3 11. Rg1 Nxf1+ 12. Rxf1 Qxh2 13. Qa4+ c6 14. cxd5 b5 15. Nxb5 cxb5 16. Qxb5+ Kd8 17. Qb7 Qc7 18. Qxa8 Bb4+ 19. Kd1 Ke7 20. dxe6 Rc8 21. Qe4 f6 22. Bf4 Qb6 23. a3 Qa6 24. Bd2 Qa4+ 25. Ke1 Bxd2+ 26. Kxd2 Qb3 27. Rab1 Rd8 28. Rfc1 {‘and W. won.’ Taken from the Cheltenham Examiner 9.9. 1909. Also published in the Birmingham Daily Post 7.9.1909.} 1-0

After an erratic opening, Black could have refuted Mrs Sidney’s unsound knight sacrifice by playing the simple 16… Nd7.

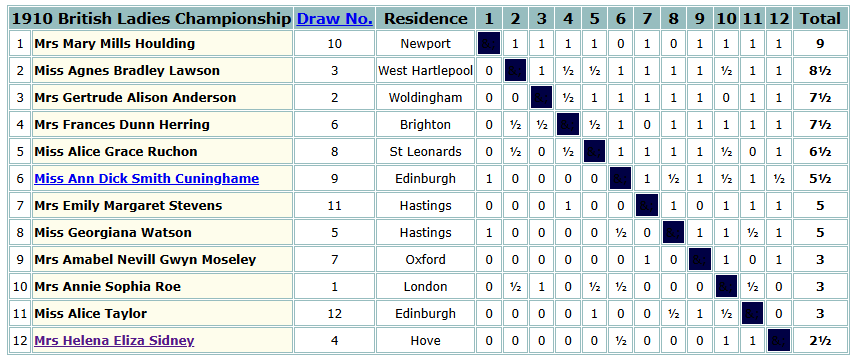

1910 took her to Oxford, where she was a lot less successful, as the crosstable below demonstrates. Perhaps she was in poor health, or perhaps the games just didn’t go her way. There were a lot of ladies of round about 1750 strength taking part in these events, all of whom were capable of beating each other on their day.

By the time of the 1911 census Mrs Sidney seemed to have decided on Helen as her first name: later records give Helen Eliza or (on electoral rolls) Helen Elise. She was still taking a few years off her age, now claiming to be 50 rather than 52. Helen and Paul employed a servant, Annie Drury, and there was also a visitor, a 76 year old spinster of private means delightfully named Lucretia Sprott.

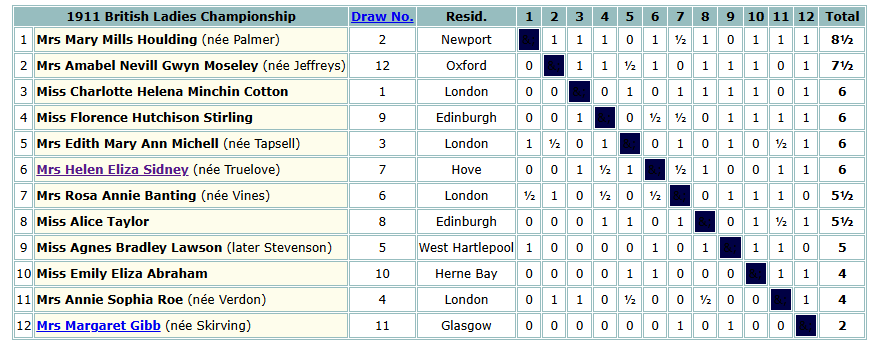

She was back on form for that year’s British Ladies Championship, which necessitated a long journey to Glasgow.

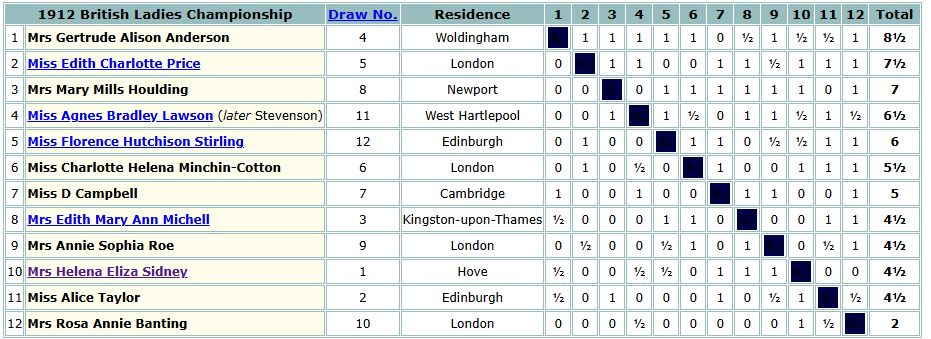

In Richmond in 1912 she finished in the lower half of the table.

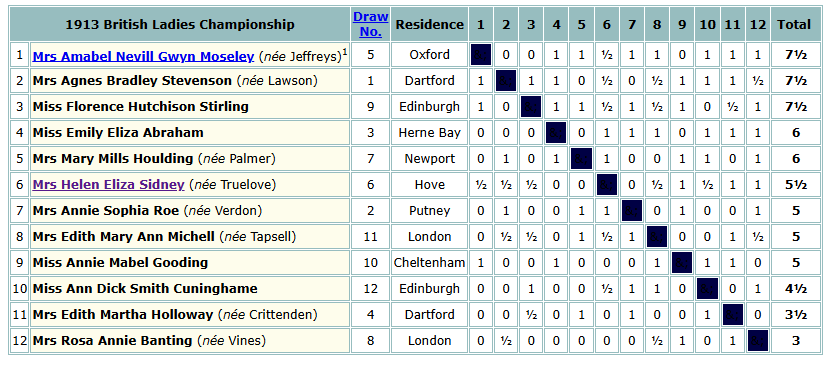

Cheltenham in 1913 would mark her last public tournament appearance, although it was by no means the end of her chess career. Perhaps her chess had mellowed with age: here she drew no less than five games, two more than anyone else in the event.

Here she is, the imposing figure seated in the centre of the photograph.

During this period, Mrs Sidney was involved in a number of lawsuits.

In 1910, Paul and Helen were accused of slander. Mrs Sidney had told a shopkeeper that the lady accompanying another customer was not his wife. The other customer demanded a retraction and apology which she refused to give, but the jury decreed that her remarks were not slanderous.

Paul died in 1914, when he was facing a lawsuit from a plumber claiming insufficient payment, and his widow took over the case. Again, the court found in her favour.

In 1917 Mrs Sidney was accused of using a neighbour’s coal cellar: this time she was ejected from court and the plaintiff was awarded damages.

The 1921 census found her visiting a friend in Hastings, claiming now to be aged 55 rather than 62, while Annie Drury was holding fort back in Hove, now at 27 rather than 17 St Aubyns. I’m not sure whether she’d moved to a different apartment or whether the houses had been renumbered.

There was little sign of her playing chess during the war years, but by 1921 she was back in action in Brighton and Hove. In 1922 she donated a trophy for schoolboys from Brighton and Hove, but it only seemed to run until 1925.

She was also continuing her late husband’s property development business: there are records in the London Gazette in 1930, 1931 and 1933 relating to the acquisition of properties in Hove.

It was at some point during the 1930s that the incident occurred that made Helen Eliza Sidney famous, at least to readers of The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict. Her faithful dog, possibly a small terrier, possibly named Mick, or Mr Cutts, or Monsieur Le Chien, was her permanent companion who accompanied her to Brighton Chess Club. No dogs were allowed, so, not wanting to upset their distinguished and generous member, Mick was elected a member of the club. This was no doubt a story that gained in the telling.

In 1938 the British Championships came to Brighton, in no small measure due to the generosity of Mrs Sidney, who made a donation of £150 towards tournament expenses. She was on hand to present the prizes, most notably to CHO’D Alexander, that year’s British Champion.

Although her days of playing in the British were long gone, she was still active locally, retaining the title of Sussex Ladies Champion as there were, sadly, no other entries. It seems that chess was becoming less popular with women.

She was still at home in the 1939 Register, again subtracting four years from her age, giving her date of birth as 7 July 1862, and still accompanied by her loyal servant Annie Drury, who also lied about her age: she was born in 1887, not 1890.

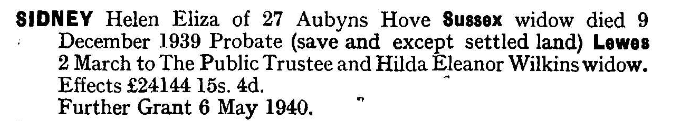

But this was to be the end of her long and unconventional life: she died on 9 December 1939. Her death record gave her age as 79: she was actually 81.

That comes out to about £2,000,000 today, excluding ‘settled land’: not bad for the daughter of a humble farm labourer.

Comparing Annie Gooding, Augusta Talboys and Helen Sidney, three provincial ladies from the early 20th century, we can see that they have quite a lot in common. All women of a certain age and class. All childless. Miss Gooding and Mrs Sidney appear, from their legal entanglements, to have been rather ‘difficult’. Mrs Talboys and Mrs Sidney were both animal lovers. Miss Gooding and Mrs Sidney were both what we might now consider average club standard players, Mrs Talboys probably a bit below their level. All had a lifelong interest in chess. All were also generous benefactors of the game which meant so much to them.

The remarkable thing about Helen Eliza Sidney, though, was her background: growing up in a time when chess was very much an upper middle-class pastime, she was a shining example of social mobility, achieved by marrying a wealthy (and much older) man. He taught her chess: at first she rebelled, but soon outstripped her husband.

The world has changed a lot in the past century, and chess has changed as well. I suspect women like Annie, Augusta and Helen were long ago lost to the more social game of bridge. But they should all be remembered and celebrated for their contribution to their favourite hobby.

I’m looking at compiling a book combining some of Chapter 1 of The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict with selected posts from this website, so will be featuring some more stars of that book in future Minor Pieces. Looking back, what we wrote about Mrs Sidney almost 40 years ago might be considered offensive in tone today: humour, as well as chess, has changed a lot in my lifetime.

Mrs Sidney has been the subject of other blog posts: these articles were very useful.

John Saunders on Helen Eliza Sidney

Batgirl (Sarah Beth Cohen) on Houlding, Herring and Sidney

Other sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

EdoChess (Rod Edwards) (Mrs Sidney)

ChessBase/Stockfish

Britbase (John Saunders)

Brighton Chess (Brian Denman: who also sent me his file of Mrs Sidney’s games)

Leave a comment