It’s time to return to Twickenham and meet the man who was the President of the second Twickenham Chess Club from its foundation in 1921 to his death in 1927.

Dr John Rudd Leeson was, as you’ll soon discover, a significant member of the Twickenham community.

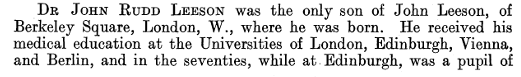

He was born in 1854 in London, the son of a doctor, receiving his medical education in London, Edinburgh, Vienna and Berlin. While in Edinburgh he was privileged to work under Joseph Lister, becoming his house surgeon. Many years later he wrote a book about his mentor: modern reprints are readily available, for example here.

By 1879 he had set up a general practice at 6 Clifden Road, Twickenham. A man of diverse interests, he threw himself into life in Twickenham, becoming involved in a wide variety of local societies.

One of his interests, of course, was chess. He was a member of the famous City of London club, drawing against Blackburne in a blindfold simul.

Here he is, in 1895, donating a prize for the Twickenham Club Championship, the year before they moved to Teddington, changing their name to the Thames Valley Chess Club.

Dr Leeson was, it seems, more of a social player, but he did take part in this friendly match against their Richmond neighbours.

Regular readers will see several familiar names in both teams. You’ll also note, the board above Leeson, none other than Richard Doddridge Blackmore, novelist (Lorna Doone) and market gardener, whom I should write more about at some point.

Here he is, at their club’s 1902 AGM at the Adelaide, at the time of writing the venue of the current Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club.

There’s not a lot more – apart from a loss by default (perhaps not surprising, given his occupation, to report for almost two decades.

Then, after the war, it was decided that there should be a new chess club in Twickenham. Leeson may have been directly involved in setting this up, and he was appointed their President.

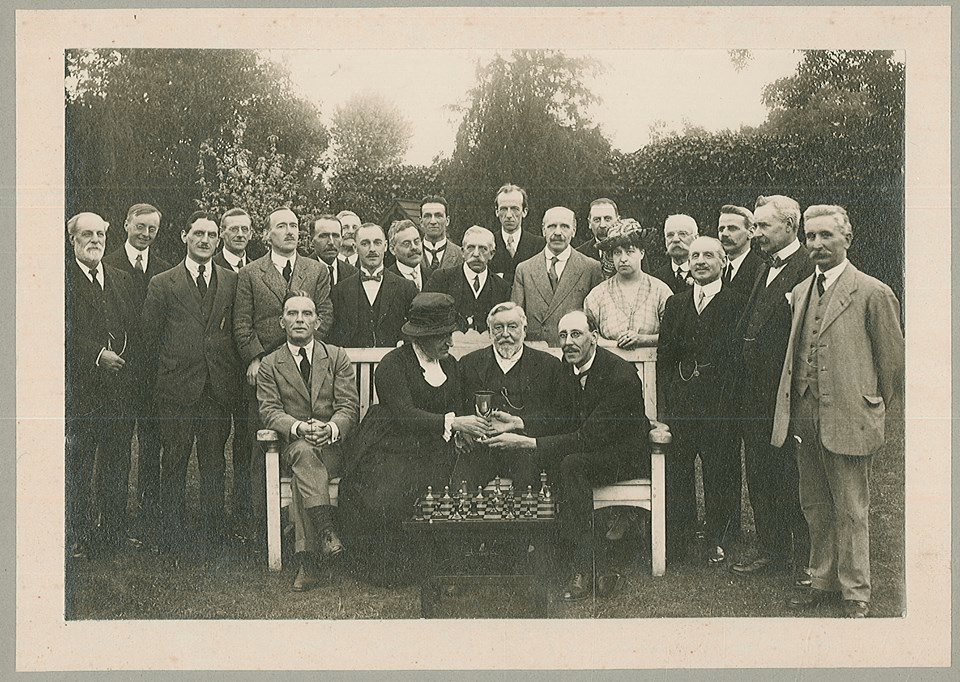

The new club opened its doors in 1921, and a few months later Dr Leeson invited its members to Clifden House, a few yards from his previous residence, where he’d lived since about 1888.

This rather wonderful photograph, I would guess, was taken at that gathering. Leeson is seated on the bench.

The following year the weather wasn’t so favourable.

There may or may not have been subsequent annual events, but if so the Richmond Herald doesn’t seem to have reported them. I also have no evidence as to whether or not Dr Leeson continued in his role as club president. I’d assume he did, but who knows?

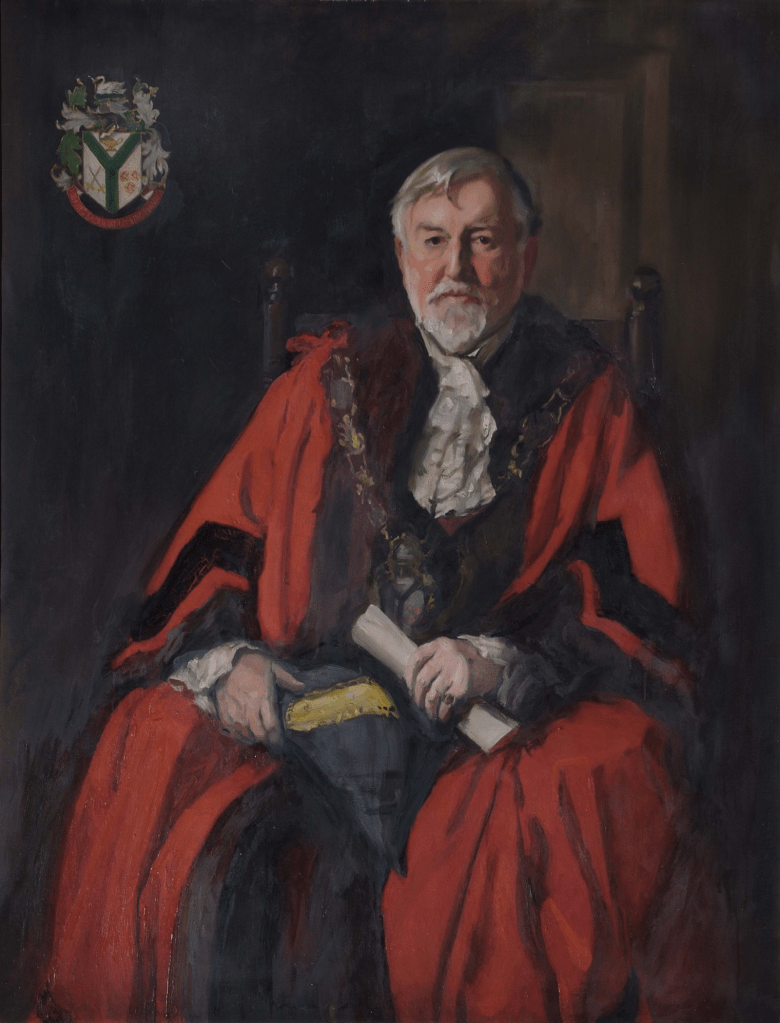

In 1926 Leeson became the first Mayor of Twickenham. Here, you can see a silent film showing some of the festivities.

https://www.londonsscreenarchives.org.uk/title/19919/

One of his daughters, Edith, was an artist, who portrayed her father in his mayoral robes here.

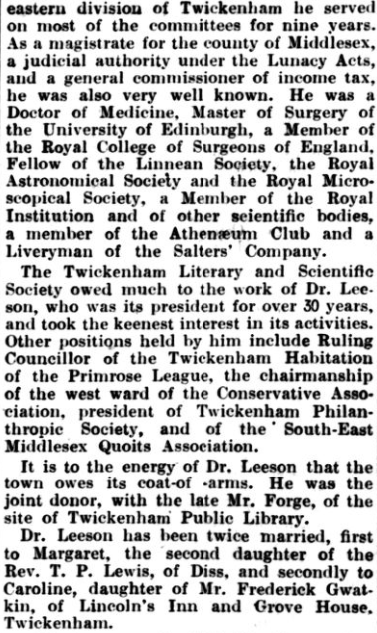

This was to be the climax of his life: he died in office on 23 October 1927. The Richmond Herald provided this obituary.

As the joint donor of the land for the current Twickenham Library, he would have been delighted to know that, almost a century after his death, it hosted a successful chess club for children.

This obituary is taken from the Royal Astronomical Society.

Volume 88, Issue 4, February 1928

An admirable life, it would appear, and typical of his time: an affluent man who was able to devote his considerable abilities to public service. In an urban area such as Twickenham you would find many like him who were, in many ways the mainstays of society, supporting local organisations as well as helping those less fortunate than themselves. Sadly, community-minded, public spirited people like Dr John Rudd Leeson seem to have become a dying, perhaps an extinct breed.

It was in part because of people like him that community organisations like chess clubs were able to flourish. Although Leeson’s interest in chess was fairly peripheral (a social player who would have devoted much more time to his many other passions), he still played an important part in the development of chess in Twickenham, firstly through membership of the first Twickenham Chess Club as it moved to Teddington and became the Thames Valley Chess Club, and then through his Presidency of the second Twickenham Chess Club in the latter part of his life.

But there was another side to him as well.

On two occasions he fell foul of the law. Here he is, in 1894, failing to notify the authorities of an infectious disease.

In 1921 he sailed his yacht to Yarmouth, on the Isle of Wight, where he came across a Free Trade meeting. As a staunch Conservative he felt it was his duty to intervene.

By 1920 he’d developed some rather strange views about what you should and shouldn’t drink. His particular bugbear concerned milk.

On the other hand he had no problem drinking sewage water.

This seems very strange coming from a former GP who had had the best possible medical training.

While harmless eccentricity is all very well, he had other views which some will find more disturbing.

According to Lyndsay Andrew Farrall’s 1969 PhD thesis Origins and Growth of English Eugenics, 1865-1925, Leeson was a member of the Eugenics Education Society. The history of eugenics is fascinating, but not something for this article. It started with Darwin’s theory of evolution and was taken up by progressive thinkers who believed that if you encouraged intelligent people to have more children and less intelligent people to have fewer children the world would become a better place. They hadn’t really thought it through, though, and support for eugenics moved to the far right, very much linked with the rise of fascism and Nazism after the First World War.

(Note: Farrall’s thesis was online when first writing this, but, by the day of publication, had disappeared. I hope it will reappear in future.)

According to Steven Woodbridge’s 2005 article The ‘Bloody Fools’: Local Fascism during the 1920s, Leeson joined the British Fascists in 1926. Woodbridge reports that the speakers in Kingston would warn listeners about the ‘threat’ from Communism and anarchism, and painted a very gloomy vision of the future of the country and the Empire. They blamed ‘aliens’ (immigrants) for unemployment, housing shortages and a decline in moral values.

That last sentence, in particular, might sound very familiar.

In November 1926 he was involved with one final controversy: the headmistress of Twickenham County Girls School, Dr Isabel Turnadge, had given birth to a son: Dr Leeson considered motherhood and employment incompatible and demanded that she should be removed from her post.

Public opinion was split on the matter. George Bernard Shaw went so far as to make the rather extreme suggestion that the members of the Twickenham Higher Education Committee should all be drowned in the Thames. James Money Kyrle Lupton, not unexpectedly, wrote to the press offering his support for their decision.

What should we make of the President of the second Twickenham Chess Club? Here was a highly intelligent and popular man who who seems to have fallen down a rabbit hole, holding views on a range of topics which were variously odd or reactionary.

It’s not hard to see a lot of parallels today.

One final link: a biography from the excellent Twickenham Museum website here. (As a side note B(rian) L(ouis) Pearce, mentioned in the bibliography, was a social chess player whom I vaguely knew many years ago.)

Join me again soon for some more tales of chess players from the past.

Acknowledgements and Sources

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Google Maps

Twickenham Museum website

Richmond Local Studies Library

Richmond upon Thames Borough Art Collection

Film London (London’s Screen Archives)

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Researchgate.net

Professor Joe Cain website

Leave a comment