One of the features of Chess Heroes: Puzzles Book 2, coming, with any luck, in the Autumn, is a section featuring puzzles taken from the major 19th century tournaments.

The Paris tournament of 1878 featured most of the world’s leading active players, but the last two places, detached from the rest of the field, were taken by two much weaker players. In 12th and last place, on 2½/22, was Karl (or Carl) Pitschel, and, a point above him, sat Henry William Birkmyre Gifford.

Gifford was born in Australia in 1847 and spent time in both the Netherlands and France before settling in London, where he died in 1924.

Neither the seemingly omniscient Edward Winter nor the hive minds of Wikipedia have any further biographical details, so, of course, I wanted to find out.

Let me take you back to the Old Bailey on 22 August 1842.

EDWARD GIFFORD and SARAH ANN HUNT were again indicted for feloniously receiving, on the 28th of February, 8 lace shawls, value 13l.; 26 lappets, value 8l.; 19 berthes, value 8l.; 81 capes, value 21l.; 83 cambric caps, value 35l.; 11 lace dresses, value 29l.; 27 falls, Value 10l.; 28 veils, value 19l.; 12 collars, value 4l.; 38 scarfs, value 30l.; and 10 muslin collars, value 4l.; the goods of Samuel Lambert; well knowing them to have been stolen; against the statute, &c.; to which

GIFFORD pleaded GUILTY . Aged 33.— Transported for Fourteen Years.

And later, on a separate charge:

HUNT.— GUILTY . Aged 27.— Transported for Fourteen Years.

Edward and Sarah were running a brothel in what is now Warwick House Street, very close to Trafalgar Square. They were not married, but living together as man and wife, sometimes under the names of Mr & Mrs Good. A man named Benjamin (or Richard) Handley (or Hanley or Manley) was employed to steal clothing and furnishings for use in their house of ill repute on their behalf.

You can read the transcript of the trial here. (You’ll note, by the way, that one of the witnesses was the splendidly named Fulgence Pigache, while schoolboys might be amused by Charlotte Handcock, who was living with the accused, quite likely working as a prostitute.)

Sarah sailed to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on board the Garland Grove, no doubt a lot less delightful than its name, departing on 7 September 1842 and arriving on 20th January 1843. With her was her 10-year-old son William, who was, according to the surgeon’s report, ‘very kind to the sick’.

Edward had longer to wait, on the Leviathan, a prison hulk in Portsmouth, before departing on the Cressy on 28 April 1843, and reaching Van Diemen’s Land on 28 August, where he was soon reunited with Sarah.

While many of the convicts sent there would have come from a background of poverty, it seems that Edward and Sarah were well off. At present I haven’t yet managed to find out about their parentage or what exactly they did in Tasmania, as it became in 1856. Did they continue with their previous occupation? With the vast majority of convicts being male, there would no doubt have been a demand.

On 1 March 1847 Sarah. pictured below, gave birth to a son named, according to official records, Henry Wm Berkmyre (sic) Hunt. On 30 August 1848, Henry was joined by a sister, Margaret Birkmyre Hunt.

Both Henry, our protagonist, and Margaret, would later use Gifford as their surname. Henry would, however, sometimes use Birkmyre as his preferred forename. Sarah was without doubt their mother, but who was their father? It might have been Edward, but it could easily have been someone else.

The name Birkmyre might be a clue. This is a rare Scottish surname, originally from the Dumfries area. It might, I suppose, have some connection with Edward or Sarah’s family, or the name of Henry and Margaret’s father. I can’t find anyone of that name in Tasmania in 1846/47, but someone could have been passing through. However, searches through all known Birkmyres from that period failed to reveal any likely candidate. (Coincidentally, or perhaps not, a girl named Agnes Birkmyre, otherwise known as Mary Beaton, arrived there as a convict in 1851. If her online trees are correct, Birkmyre, remarkably, really was her father’s name. It could well be, though, that they have the wrong person, and that she developed some connection with Edward and Sarah.)

Margaret’s first marriage produced three sons, whose families still live in Tasmania today, so perhaps a DNA test might reveal something. Here she is, later in life.

In 1852 Edward received an official pardon, perhaps because he was now a respected member of Tasmanian society.

On 2 October 1854 another son was born, given the name Edward Enos Gifford. His birth record gives Sarah Ann Hunt as his mother and Enos Gifford as his father: this must have been Edward, but it seems he also used the names Enos and Aeneas. Here’s Edward junior, again from online family trees.

We can pick Edward Gifford senior up again when, in 1870 and again in 1874, he was the victim of crimes.

In both cases many items (clothing, jewellery, tableware and so on) were stolen from his property, but later recovered. On the latter occasion, Elizabeth Gear was charged with theft.

The nature of the items suggest that he and Sarah might possibly still have been in the same business, but who knows?

Edward died in Hobart on 18 January 1883: here he is pictured towards the end of his life.

But what happened to Henry William Birkmyre Gifford, the real subject of this article?

Why did he move to Europe? When and how did he learn chess?

For a clue, let’s return to the Old Bailey, this time on 23 February 1846.

EDWARD BRYANT GAREY was indicted for feloniously forging and uttering a certain instrument in the form of an instrument made by John Reid the elder, being Clerk of the Report-office of the High Court of Chancery purporting to be an office copy of a certificate of William Russell, esq., Accountant-General of the said Court, that Thomas Jones Bellamy and Charles James Foster had paid into the Bank of England 2,596l. 17s., pursuant to an order of the said Court of Chancery; and also an office copy of a receipt of one W. R. West, for the Governor and Company of the Bank of England, for Paying of the said sum into the Bank of England, with intent to defraud Thomas Jones Bellamy and Charles James Foster.—Fourteen other COUNTS, varying the description of the instrument.

The complete transcript is here.

GUILTY . Aged 51.— Transported for Fifteen Years.

Again, not the usual poachers or petty criminals, but a respectable middle-aged solicitor found guilty of forgery and fraud.

He sailed on the John Calvin, leaving London on 9 May 1846 and arriving in Van Diemen’s Land on 21 September. He had to leave his family back at home, including a daughter, Eliza, who was married to Neville Davison Goldsmid, and another daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, who was married to Neville’s brother Edmund Elsden Goldsmid. The Goldsmid brothers were members of a prominent Anglo-Jewish family who had both Dutch and French connections, although by that time Neville, at least, had converted to Christianity.

Neville, a wealthy businessman and art collector (his collection included a Vermeer) lived in The Hague and was a member of the chess club there. It seems likely that he was one of the sponsors of the first three unofficial Dutch Championships.

I would speculate that Edward Garey had introduced Edward Gifford to the Goldsmid family, and that they were in touch in some way. Garey didn’t have that long in Tasmania, dying on 18 October 1852, but the Goldsmid connection would continue for many years.

I suspect it was because of his family’s friendship with the Goldsmids that Henry Gifford travelled to Europe, perhaps living with Neville and Eliza, who had married in 1850 but had no children of their own. It’s possible that he left Tasmania early in life, his parents thinking that living with a wealthy family would be better for him than what may well have been an unstable family life in Hobart. It could also have been, if the Giffords, Gareys and Goldsmids had kept in touch, much later. I can find no matching shipping records for Gifford, Birkmyre or Hunt to help me.

Maybe Neville taught Henry chess, and, seeing the young man’s talent, helped to promote some tournaments for him to take part in.

We first meet Henry over the chessboard in 1873, living in The Hague (Den Haag or ‘s-Gravenhage if you prefer) but visiting Rotterdam in February where we have two recorded games against Charles Dupré: a loss and a win.

[Event “Casual Game: Rotterdam”]

[Date “1873.02.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Dupré, Charles EA”]

[Result “1-0”]

[ECO “C37”]

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 g5 4. Bc4 g4 5. Ne5 Qh4+ 6. Kf1 Nh6 7. d4 f3 8. g3 Qh3+ 9. Kf2 Bg7 10. Bf1 Qh5 11. Nc4 Nc6 12. c3 d6 13. Bf4 Bd7 14. Ne3 O-O-O 15. Na3 Rhe8 16. Bd3 f5 17. Qc2 Rf8 18. Nd5 Be6 19. Nxc7 Kxc7 20. Nb5+ Kc8 21. Nxd6+ Rxd6 22. Bxd6 Rd8 23. Bf4 fxe4 24. Bxe4 Bf5 25. Rae1 Bg6 26. Qb3 Bf7 27. Qa4 Bd5 28. Qb5 Qf7 29. b3 Nf5 30. Qd3 Bxe4 31. Rxe4 Nd6 32. Bxd6 Rxd6 33. Rxg4 Ne5 34. Qe4 Nxg4+ 35. Qxg4+ Kc7 36. Re1 Bh6 37. Re5 Rf6 38. Qe4 Kd6 39. c4 Bf8 40. Rb5 b6 41. Qa8 Qc7 42. Qe8 Qe7 43. Qb8+ Qc7 44. Rd5+ Kc6 45. Qa8+ Qb7 46. Qe8+ 1-0

That August he took part in the first unofficial Dutch Championship, held in his home town.

He didn’t just take part: he won, sharing first place and capturing the title after a play-off. A book of the event was published so most of his games are available.

There can be no better way to start your competitive chess career than with a queen sacrifice, and that’s what happened in his first round game.

[Event “NED SB-01 Congress: The Hague R1”]

[Date “1873.08.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Ter Haar, TC”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 d5 4. exd5 Qxd5 5. c4 Qe4+ 6. Be3 exd4 7. Bd3 Qe7 8. Nxd4 Nxd4 9. O-O Ne6 10. Nc3 c6 11. Re1 Bd7 12. Bf4 Nf6 13. Bg3 g6 14. f4 Bg7 15. Kh1 Nh5 16. Ne4 Nxg3+ 17. Nxg3 O-O-O 18. f5 gxf5 19. Nxf5 Qf6 20. Nd6+ Kb8 21. Rf1 Nf4 22. c5 Qg5 23. Qd2 Qd5 24. Qxf4 Qxd3 25. Ne8+ Ka8 26. Nc7+ Kb8 27. Na6+ Ka8 28. Qb8+ Rxb8 29. Nc7#

You must admit he was lucky, though. He lost a piece in the opening, but his opponent blundered into a smothered mate.

In this game he gave up a pawn in the opening without obvious reason but later sacrificed to drive the enemy king to the far corner of the board.

[Event “NED SB-01 Congress: The Hague R5”]

[Date “1873.08.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Meijers, H”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. d4 b6 2. e4 Bb7 3. Nc3 e6 4. a3 Nf6 5. Bf4 Bxe4 6. f3 Bc6 7. Bd3 Nd5 8. Nxd5 Bxd5 9. c4 Bc6 10. Qc2 d5 11. O-O-O Qd7 12. cxd5 Qxd5 13. Be4 Qd7 14. d5 exd5

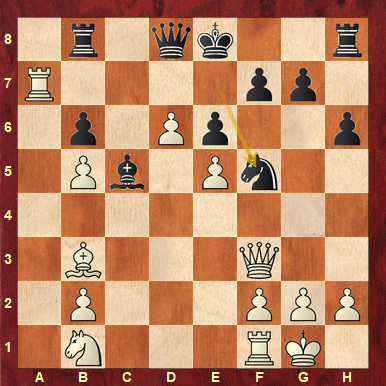

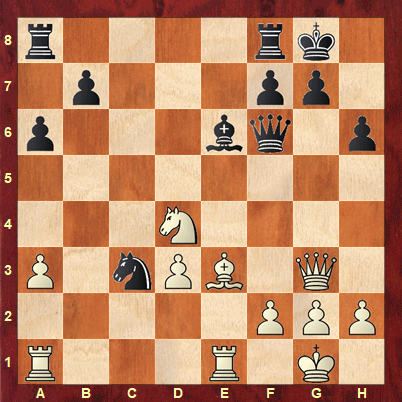

In this position, White against J Andriessen in Round 6, he had a choice of sacrifices.

Gifford forced Black’s resignation after 18. Bxe6 fxe6 19. Qh5+, but 18. Rxf7 would also have done the job.

He brought off another sacrificial finish here.

[Event “NED SB-01 Congress: The Hague R8”]

[Date “1873.08.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Kamphuizen, W”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. c3 Nf6 5. d4 exd4 6. e5 d5 7. Bb5 Ne4 8. cxd4 Bb4+ 9. Bd2 Bxd2+ 10. Nbxd2 Nxd2 11. Qxd2 Bd7 12. Bxc6 Bxc6 13. O-O O-O 14. Rae1 Bd7 15. Re3 c6 16. Ne1 Be6 17. Nd3 Qc7 18. f4 g6 19. f5 Bxf5 20. Rxf5 gxf5 21. Rg3+ Kh8 22. Qh6 f6 23. exf6 Rf7 24. Ne5 Raf8 25. Ng6+ 1-0

Against the eventual joint winner he won a pawn in the opening using a stock tactic, and, attacking powerfully, had no difficulty bringing home the full point.

[Event “NED SB-01 Congress: The Hague R9”]

[Date “1873.08.??”]

[White “Blijdenstein, Benjamin Willem”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. O-O Nf6 5. d3 h6 6. a3 d6 7. b4 Bb6 8. h3 Qe7 9. Nh4 Nxe4 10. dxe4 Qxh4 11. Qf3 Be6 12. Be2 Nd4 13. Qd3 O-O 14. Nd2 f5 15. Bf3 f4 16. c3 Nc6 17. Qe2 Rf6 18. Bh5 f3 19. Bxf3 Raf8 20. Kh2 Ne7 21. Nc4 Bxh3 22. Ne3 Rxf3 23. Qxf3 Bg4+ 24. Qh3 Bxh3 25. gxh3 Rxf2+ 26. Rxf2 Qxf2+ 0-1

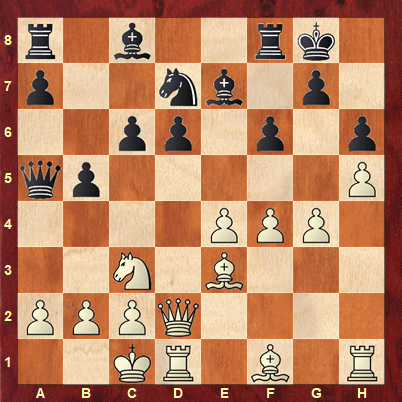

In Round 11, White against Julius de Vogel, he reached this position after 5 moves.

He had a winning tactic here: 6. Bxf7+ Kxf7 7. Qh5+, but instead played 6. Nxc6, which Black should have met with Qf6. After 6… bxc6, though, he didn’t need a second invitation. 7. Bxf7+ won him a pawn and, eventually, the game.

Gifford needed to win his 13th and last round game with the black pieces, which was achieved when his opponent, Cornelis P Hofstede de Groot, miscalculated in this position.

24. bxc5 would have been equal, but the game continued 24. e5 cxd4 25. exf6 dxe3 26. Kg2 exd2 27. Rxd2 Bc6+ 28. Kh3 Nxf4+ 29. gxf4 Re3+, leaving Black a piece ahead with a comfortable win.

White against Blijdenstein in the play-off, he failed to take advantage when his opponent fell for an opening trap which was well known even back in 1873: 1. d4 d5 2. c4 dxc4 3. e3 b5 4. a4 c6 5. axb5 cxb5, when 6. Qf3 is immediately decisive. Gifford played Nc3 instead, but he still won the game and the title.

The impression we get from these games is that Gifford was a highly talented tactician who, with more experience, had the potential to reach master level.

In September 1873 Steinitz visited The Hague, playing this short but exciting game against Gifford. Some sources give it as a game from a simultaneous display, but Tim Harding (Steinitz in London) thinks it more likely it was a one-to-one encounter.

[Event “Casual Game: The Hague”]

[Date “1873.09.24”]

[White “Steinitz, Wilhelm”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 g5 4. Bc4 g4 5. Ne5 Qh4+ 6. Kf1 f3 7. d4 Nf6 8. Nc3 fxg2+ 9. Kxg2 Qh3+ 10. Kg1 Bg7 11. Nxf7 Rf8 12. e5 Nh5 13. Ne4 h6 14. Nxh6 d5 15. Bxd5 Nf4 16. Bxf4 Rxf4 17. Ng8 Qe3+ 18. Kg2 Qh3+ 1/2-1/2

It’s perhaps not surprising that he decided to turn his hand to the composition of chess problems.

Sissa 1873

This is a selfmate in 4 moves, a type of problem rather more popular then than it is now. For those unfamiliar with the genre, in a selfmate White has to compel a reluctant Black to mate him in the specified number of moves. So you’re trying to restrict Black’s moves and ensure that he has no choice but to mate you on the fourth move. You’ll find the solutions to all problems herein at the foot of the article.

The following year witnessed Gifford’s most famous game. Blackburne paid a visit to The Hague, winning this casual encounter which has been much anthologised over the years. There are several versions of the last few moves: this is the one preferred by ChessBase.

[Event “Casual Game: The Hague”]

[Date “1874.??.??”]

[White “Blackburne, Joseph Henry”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 exd4 4. Bc4 Bc5 5. Ng5 Nh6 6. Qh5 Qe7 7. f4 O-O 8. O-O d6 9. f5 d3+ 10. Kh1 dxc2 11. Nc3 Ne5 12. Nd5 Qd8 13. f6 Ng6 14. fxg7 Kxg7 15. Qxh6+ Kxh6 16. Nxf7+ Kh5 17. Be2+ Kh4 18. Rf4+ Nxf4 19. g3+ Kh3 20. Nxf4#

Gifford should have preferred d5 on either move 7 or move 8. Blackburne’s queen sacrifice was spectacular but gratuitous as he was winning anyway.

That year, in Amsterdam, Gifford again tied for first place in the unofficial Dutch championship, but this time lost the play-off to Adriaan de Lelie.

Again, most of the games were published in the Dutch yearbook: thanks to Gerard Killoran for pointing me towards this. Gifford was little troubled in the early rounds, where his opponents lost material to simple tactics early on.

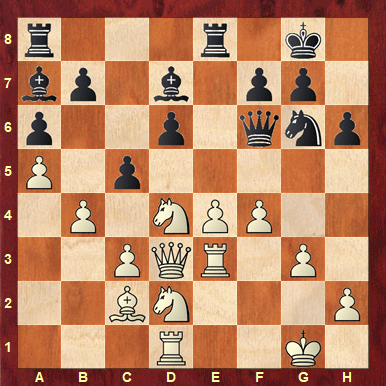

White against JP Blank, the game continued 14. h5 (missing 14. Bxb5 cxb5 Qd5+) 14… Qa5 15. Kb1 (again Bxb5 worked) 15… Nb6, allowing another Stock Tactic, which this time Gifford found: 16. Nd5 Qxd2 17. Nxe7+ Kf7 18. Rxd2 Kxe7 19. e5 fxe5 20. fxe5 dxe5 21. Bc5+.

He had more trouble playing White against GFW Baehr, who had held onto the gambit pawn successfully. Simplest now was 26… d5, but Baehr mistakenly offered a queen trade: 26… Ng8. Gifford should, in theory, have traded queens after which Rfd1 would regain the pawn. Instead he played the speculative 27. f6, when Black might have tried 27… Qe3+ 28. Kh1 g6. 27… Nxf6 would have given White attacking chances, but the foolish 27… f6 lost at once to 28. Nf5.

Two pieces up against TC Ter Haar, he carelessly threw away a winning advantage, playing 29… Rg1, overlooking 30. Qf8+. The game was eventually drawn.

He played an exciting game against the previous year’s joint winner, resulting in a sharp ending in which both players missed chances.

[Event “NED SB-02 Congress Amsterdam R8”]

[Date “1874.??.??”]

[White “Blijdenstein, Benjamin Willem”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. h3 f5 2. d4 Nf6 3. c4 d5 4. cxd5 Qxd5 5. Nc3 Qd8 6. Nf3 e6 7. Bf4 Nd5 8. Be5 Nc6 9. e3 Nxe5 10. Nxe5 Qf6 11. Bb5+ c6 12. Nxc6 Nxc3 13. bxc3 Bd7 14. Qa4 bxc6 15. Bxc6 Rd8 16. Bxd7+ Rxd7 17. Rb1 Bd6 18. Rb7 Qd8 19. Rxa7 Ke7 20. c4 Rxa7 21. Qxa7+ Qc7 22. Qxc7+ Bxc7 23. Kd2 Ra8 24. Ra1 Ra3 25. Kc2 Ba5 26. c5 Rc3+ 27. Kb2 h5 28. Rc1 Rxc1 29. Kxc1 g5 30. f3 Kd7 31. Kc2 Kc6 32. e4 f4 33. Kb3 e5 34. Kc4 exd4 35. Kxd4 Bb4 36. Ke5 Ba5 37. Kf5 Bd8 38. h4 gxh4 39. Kxf4 Kxc5 40. Kf5 Kd4 41. e5 Ke3 42. a4 Kf2 43. e6 Kxg2 44. a5 h3 45. a6 h2 46. a7 h1=Q 47. a8=Q Qh3+ 48. Ke5 Qg3+ 49. f4+ Qf3 50. Qxd8 Qe3+ 51. Kf5 Qh3+ 52. Ke5 Qe3+ 53. Kd6 Qxf4+ 54. Kd7 Qd4+ 55. Ke7 Qg7+ 56. Ke8 Qh8+ 1/2-1/2

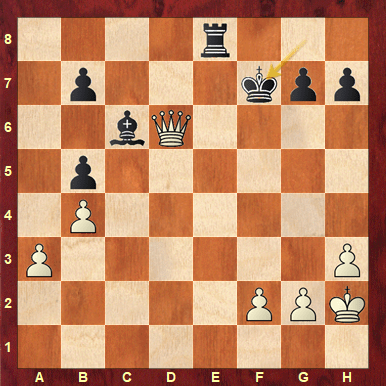

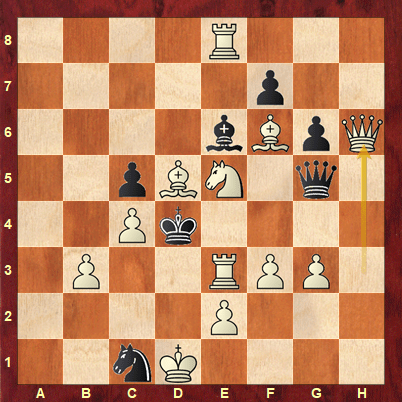

He inexplicably agreed a draw in a winning position against De Lelie.

Here’s the final position, with Gifford (White) to play. Stockfish suggests 39. a4 and if 39… bxa4 then 40. b5 Bxb5 41. Qd5+.

As a result of this game he was forced into a play-off which he lost rather horribly.

[Event “NED SB-02 Congress Amsterdam Play-off”]

[Date “1874.??.??”]

[White “De Lelie, Adrianus Adam Gerardus”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 b5 5. Bb3 d6 6. c3 Be7 7. d4 exd4 8. cxd4 Bd7 9. O-O h6 10. Nc3 Bg5 11. Be3 Nge7 12. Bxg5 hxg5 13. Nxg5 d5 14. exd5 Nxd5 15. Nxf7 Qh4 16. Nxh8 O-O-O 17. Nf7 Nf4 18. Nxd8 Nxd4 19. Bd5 1-0

In the third championship the following year Gifford this time finished in sole first place on 8/9, half a point ahead of Charles Dupré.

He won this game in the first round.

[Event “NED SB-03 Congress Rotterdam R1”]

[Date “1875.??.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Blank, JP.”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 d6 4. Bxc6+ bxc6 5. d4 exd4 6. Nxd4 Bb7 7. Nc3 h6 8. f4 Be7 9. O-O Nf6 10. h3 O-O 11. Nf3 Nh7 12. Qd3 a5 13. Ne2 Ba6 14. Qd1 Bxe2 15. Qxe2 Qb8 16. b3 Qb7 17. Bb2 Bf6 18. e5 dxe5 19. fxe5 Be7 20. Kh1 Rad8 21. Nd4 Bc5 22. Nf5 Ng5 23. h4 Ne6 24. Qg4 Kh7 25. Rf3 Qb6 26. Raf1 Rd7 27. Bc1 Bd4 28. Nxh6 Bxe5 29. Nxf7 g6 30. Nxe5 1-0

His only defeat also involved a knight sacrifice on KR6.

[Event “NED SB-03 Congress Rotterdam R3”]

[Date “1875.??.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Stolte, GM.”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. e3 c5 4. Nf3 Nc6 5. a3 a6 6. Nc3 Nf6 7. Bd3 dxc4 8. Bxc4 b5 9. Ba2 c4 10. e4 Bb7 11. O-O Ne7 12. Qc2 Ng6 13. h3 Be7 14. Be3 O-O 15. Rad1 Ne8 16. Qe2 Rc8 17. Bb1 f5 18. exf5 exf5 19. Bc1 Nc7 20. Nh2 Qd6 21. f3 Rce8 22. Qc2 Bd8 23. Ne2 Nd5 24. f4 Ne3 25. Bxe3 Rxe3 26. Qd2 Rfe8 27. Nc3 Nxf4 28. Be4 R3xe4 29. Nxe4 Rxe4 30. Rfe1 Nxh3+ 31. Kh1 Bc7 32. Nf3 h6 33. Rf1 Rh4 34. Qe1 Nf2+ 35. Kg1 Nxd1 36. Qxh4 Nxb2 37. Ne5 Qd5 38. Rf2 Bb6 39. Qh5 Qe6 40. Rxf5 Bxd4+ 41. Kh1 Be4 0-1

In 1876 the unofficial Dutch Championship, in Gouda, was run as a knock-out tournament of 9 players. Perhaps Neville Goldsmid’s death the previous year meant that funds were no longer available for an all-play-all event. Gifford was eliminated by the amusingly named Christiaan Messemaker in the first round. You’ll note that he was 20 or so years older than many of his opponents in these events.

In 1877, Henry Gifford’s life changed. In the second quarter of that year the widowed Eliza Goldsmid married Henry Gifford in London. She had been born in 1829, so was 18 years older than her new husband. The happy couple decided to set up home in Paris, where Eliza’s widowed sister Sarah (her husband Edmund Goldsmid had died in 1870) lived.

In 1878 a major international tournament took place in Paris in conjunction with the World Expo, and, either because of his successes in the Netherlands or because he was living in Paris at the time, Henry William Birkmyre Gifford was invited to take part.

Here’s a photograph of some of the participants, along with Steinitz, present as a journalist.

https://www.europe-echecs.com/art/le-tournoi-de-paris-1878-7231.html

Gifford is the tall gentleman standing second from the left. He was described in the press at the time as being from ‘London and Paris’.

As you can see, he was rather out of his depth against world class opposition, managing just 3½/22.

He took a game off both Anderssen and Clerc, while scoring a win and a draw against his fellow struggler Pitschel.

In his first game he missed a win against Clerc, but made no mistake in the return encounter, sacrificing the exchange in the opening and winning in style.

[Event “Paris International Congress R1”]

[Date “1878.06.19”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Clerc, Albert”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Bd3 c5 5. dxc5 d4 6. a3 Qa5 7. axb4 Qxa1 8. Nb5 Na6 9. Nd6+ Kf8 10. Bxa6 bxa6 11. Nf3 Bd7 12. O-O Ne7 13. Nxd4 Qa4 14. Qf3 Be8 15. Nxe6+ Kg8 16. Nc7 Qd7 17. Nxa8 Kf8 18. Rd1 Nc6 19. Nxe8 Qxe8 20. Nc7 Qc8 21. Qf4 f6 22. Qd6+ Ne7 23. Nd5 Qe8 24. Nxe7 Qxe7 25. Qb8+ 1-0

A moment of carelessness cost him this game against Blackburne.

He played 18. f5 here, overlooking the obvious threat of Qxf1+.

Although past his best, Anderssen was still a formidable opponent. Here’s Gifford’s win, demonstrating that he had positional as well as tactical skills.

[Event “Paris International Congress R6”]

[Date “1878.07.05”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Anderssen, Adolf”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Bb5 Nf6 5. Nd5 Bc5 6. d3 h6 7. O-O O-O 8. Be3 Bxe3 9. Nxe3 d6 10. Qd2 Nh5 11. Bc4 Ne7 12. d4 Ng6 13. dxe5 dxe5 14. Qc3 Re8 15. Rad1 Bd7 16. Qb3 Rf8 17. Rd2 Qc8 18. Rfd1 Bc6 19. Bd5 Nf6 20. Bxc6 bxc6 21. Qc4 Qb7 22. b3 Rae8 23. Ne1 Re6 24. Nf5 c5 25. f3 Rc6 26. Rd8 Ne8 27. R1d7 Qb4 28. Qxb4 cxb4 29. Rc8 f6 30. Re7 Nd6 31. Rxg7+ Kh8 32. Rcxc7 Rxc7 33. Rxc7 Nb5 34. Rb7 a6 35. Rb6 Nf4 36. Nxh6 Kh7 37. Ng4 Kg7 38. Ne3 Rd8 39. g3 Ne2+ 40. Kg2 Rd2 41. Kh3 Ng1+ 42. Kg4 Rxh2 43. N1g2 Nh3 44. Rb7+ Kg8 45. Nh4 Nd4 46. Kh5 Nxf3 47. Nxf3 1-0

Black against Mackenzie, he had a difficult decision to make here.

45… Rxg7 should hold, but Gifford erred with 45… Bxg7, when 46. Bh6 was winning for White. It’s not so easy to calculate that he can eventually escape the checks, though.

Here, he was White, facing one of Bird’s eccentric openings.

He decided on 10. Bg5, losing a piece to Nd4. Schallopp in the tournament book called it a sacrifice, but I rather suspect it was just a blunder.

His win against Pitschel was another good positional game.

[Event “Paris International Congress R9”]

[Date “1878.07.15”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Pitschel, Karl”]

[Result “1-0”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 3. Bc4 Nc6 4. d4 Bg4 5. Be3 Qf6 6. c3 Nge7 7. d5 Nd8 8. Nbd2 a6 9. h3 Bxf3 10. Nxf3 h6 11. Qa4+ c6 12. Bb6 Qg6 13. Bf1 Qf6 14. O-O-O g5 15. dxc6 Ndxc6 16. Bc7 Nc8 17. Bb5 N8a7 18. Bxc6+ Nxc6 19. Qb3 b5 20. Qd5 Kd7 21. Bb6 Qe6 22. Rd2 Qxd5 23. Rxd5 Re8 24. Rhd1 Re6 25. Bc5 Kc7 26. Ba3 Rf6 27. R1d2 Re6 28. Ne1 h5 29. Nc2 g4 30. hxg4 hxg4 31. Ne3 Rg8 32. Nf5 Rgg6 33. Kc2 Na7 34. R2d3 Nc8 35. Bb4 Kc6 36. Ba5 Rg8 37. c4 bxc4 38. Rc3 Nb6 39. Bxb6 Kxb6 40. Rxc4 Rgg6 41. Rb4+ Ka7 42. Ra4 Re8 43. Rda5 Rc8+ 44. Kd3 Rc6 45. Rc4 Rc5 46. b4 Rxa5 47. bxa5 Rf6 48. Rc7+ Kb8 49. Rc6 Kb7 50. Rb6+ Ka7 51. Kc4 g3 52. f3 1-0

In their return encounter, Gifford did well to hold the draw after losing a pawn.

He miscalculated something in this game with Black against Mason.

The obvious 42… Qxf1 offers equal chances according to Stockfish, but he tried for more with 42… Nf2, overlooking that 43. Ng3, ready to capture if Black plays Ne4 at any point, refuted his idea, leaving Mason a piece ahead.

With the black pieces against Englisch in the last round he blundered on move 8.

8… h6 was playable, but the immediate 8… Ng6 lost a pawn, and, eventually, the game after the stock tactical idea 9. Ng5.

After this tournament, Gifford went into chess hibernation. Perhaps this result had dampened his enthusiasm, or perhaps he was too busy enjoying married life.

He returned in November 1881, taking part in the second unofficial French Championship, a double round tournament with seven participants. His final score was 4½/12, for a share of 5th place.

Two of Gifford’s games were published in contemporary sources

White against Clerc in a level position, he carelessly played 23. Nxe6, and had to resign after the zwischenzug Ne2+.

This game he drew with the tournament winner resulted in a perpetual check after he missed a few chances (16… Kb8, 19… Rd6).

[Event “2nd French Championship: Paris”]

[Date “1881.11.23”]

[White “Chamier, Edward”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. O-O d6 5. c3 Nf6 6. d4 exd4 7. cxd4 Bb6 8. Nc3 Bg4 9. Be3 Qe7 10. Re1 O-O-O 11. Nd5 Qxe4 12. Nxb6+ axb6 13. Qa4 Bxf3 14. gxf3 Qxf3 15. Bf1 d5 16. Rac1 Rhe8 17. Rxc6 bxc6 18. Qxc6 Qg4+ 19. Kh1 Qe4+ 20. Kg1 Rd6 21. Qa8+ Kd7 22. Bb5+ Ke7 23. Bxe8 Qg4+ 24. Kf1 Qh3+ 25. Kg1 Qg4+ 26. Kf1 Qh3+ 1/2-1/2

Gudju was a Romanian law student whose son Ion was one of the 15 founders of FIDE. The scoresheet of his win against Gifford survived.

Gifford, playing Black, won a piece, but only had one way to defend this position.

37… Kg7 was the only winning move: after 37… Qf5 he must have missed 38. Qh6+ Kg8 39. Rg4+, forcing mate.

This was to be Gifford’s last tournament, although he maintained his interest in chess throughout his life.

In 1882 he returned to composition, having two problems published in a French magazine.

This mate in 2 has a double pin mate after a king flight.

La Vie Moderne 1882

This mate in 3 features a generous key and a king switchback in one variation.

La Vie Moderne 18-02-1882

Here’s a casual game from 1882 against visiting American Preston Ware. Ware, like Bird, was noted for his eccentric opening choices: here we have an early example of 1. b4. Ware was better most of the game, but let his position slip.

[Event “Casual Game: Paris”]

[Date “1882.??.??”]

[White “Ware, Preston”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. b4 e5 2. Bb2 f6 3. a3 d5 4. e3 Bd6 5. c4 dxc4 6. Bxc4 Ne7 7. Ne2 Bf5 8. d4 exd4 9. Nxd4 Qd7 10. O-O Nbc6 11. Nc3 Nxd4 12. Qxd4 Be6 13. Rfd1 Rd8 14. Bxe6 Qxe6 15. Qxa7 O-O 16. Qxb7 Qb3 17. Rab1 Be5 18. Rdc1 Rd3 19. Ba1 Qxa3 20. Nb5 Qa2 21. Nd4 Rd2 22. Qf3 Ng6 23. g3 Bd6 24. Nb3 Ne5 25. Qg2 Re2 26. Nd4 Rd2 27. Bc3 Nd3 28. Ra1 Rxf2 29. Rxa2 Rxg2+ 30. Kxg2 Nxc1 31. Rd2 Ra8 32. Nb5 Na2 33. Nxd6 Nxc3 34. Rc2 Ra2 35. Rxa2 Nxa2 1/2-1/2

Primary source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 24 May 1882, page 247, which states that Gifford proposed a draw as he had to leave, but that he could have won the game: Stockfish agrees.

Secondary source: https://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/1b4b5.html

He was still in Paris in 1885, taking a board against Zukertort in a blindfold simul.

[Event “Blindfold Simultaneous Display: Paris”]

[Date “1885.04.24”]

[White “Zukertort, Johannes Hermann”]

[Black “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Result “1/2-1/2”]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. Bb5 Bb4 5. O-O d6 6. Nd5 Ba5 7. c3 Bd7 8. d4 a6 9. Ba4 b5 10. Bc2 h6 11. b4 Bb6 12. Nxb6 cxb6 13. dxe5 dxe5 14. h3 Qc7 15. Be3 Rd8 16. Qe2 Bc8 17. Nd2 O-O 18. f3 Nxb4 19. cxb4 Qxc2 20. Rfc1 Qd3 21. Qf2 Be6 22. Nf1 Rc8 23. Bxb6 Rxc1 24. Rxc1 Nd7 1/2-1/2

By 1886 the Giffords had relocated to London, where Henry played his old friend Blackburne at Simpsons. It was reported (The Field 09-08-1909) that he played regularly against both Steinitz and Zukertort there as well.

[Event “Casual Game: Simpson’s Divan”]

[Date “1886.??.??”]

[White “Gifford, Henry William Birkmyre”]

[Black “Blackburne, Joseph Henry”]

[Result “0-1”]

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Bc4 b5 4. Bxb5 Qh4+ 5. Kf1 f5 6. Qe2 Nf6 7. exf5+ Be7 8. Nc3 Bb7 9. Nf3 Qh5 10. d3 O-O 11. Bc4+ d5 12. Bb3 Bd6 13. Qe6+ Kh8 14. Nxd5 Nbd7 15. Nxf6 Nxf6 16. Qe2 Nd5 17. Bxd5 Bxd5 18. Bd2 Bc5 19. Re1 Qxf5 20. Qe5 Qd7 21. h4 Rae8 22. Qc3 Be3 23. Rh3 Qg4 24. Re2 Bxf3 25. Rxf3 Qxh4 26. Rh3 f3 27. Rxh4 fxe2+ 28. Kxe2 Bd4+ 29. Re4 Rf2+ 30. Ke1 Rxe4+ 31. dxe4 Bxc3 32. Bxc3 Rxg2 0-1

Gifford was holding his own until overlooking Blackburne’s temporary queen sacrifice on move 26.

Primary source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle 15-07-1887

Secondary source: https://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter38.html (Item 5156)

We then pick Henry and Eliza up in the 1891 census, living at 11 Sydenham Avenue, Beckenham, which is very close to Crystal Palace. This would have been a rather grand house, but, assuming the numbering hasn’t changed, there’s now a block of flats there. Eliza was now styling herself Eliza Birkmyre Gifford and lying about her age, claiming she was only 50, rather than 61. Henry was described as ‘living on own means’ and they were employing two servants, a housemaid and a cook.

At this time of his life, Henry was playing little or no chess. We know that, during the late 1890s he and Eliza frequently visited the Grand Hotel at Bath. Perhaps she was taking the waters for health reasons, but if so it was to no avail as she died on 25 October 1900, leaving £6427 5s.

By the time of the 1901 census Henry was living on his own at the same address, still employing a housemaid and a cook.

In 1904 he made a brief return to the chessboard, visiting the Brighton Chess Week where he took on his old friend Blackburne in a simul, this time drawing his game.

(I note, by the way, that 9-year-old Master E Cozens, the youngest known chess player in Sussex, took part in the Junior Open tournament, and was introduced to Emanuel Lasker, who also visited the event. This would appear to be Ebenezer Henry Cozens, who died young in 1928.)

By 1911 Henry had remarried, to Lizzie Isabel Goldsmid, the niece of Eliza, the daughter of Edmund and Sarah, and the granddaughter of Edward Bryant Garey. I haven’t been able to find a marriage record, but it’s possible they married in France, where Lizzie had been born.

They’d also moved in to London, to 12 Langham Mansions, Earls Court, and still had two servants, sisters from Colchester. The next decade, under the shadow of world war, seems to have been uneventful. They were still at the same address a decade later, but this time not employing servants.

Lizzie died on 5 July 1923: her effects were valued at £4479 13s 6d. Henry followed less than a year later, on 13 April 1924.

315 Chiswick High Road is near Turnham Green. There are modern buildings there now but in 1925 it was given as the address of a builder and decorator. There might have been a private clinic there as well.

What should we make of Gifford as a chess player? EdoChess rates him just above 2200, which sounds about right. He scored heavily against relatively weak opposition in his Dutch tournaments, but was no match for the leading players of his day in Paris. His best games make a good impression: he had tactical ability but was also able to play more positionally. His problem seems to have been carelessness and perhaps impulsiveness, along with some rather inconsistent opening knowledge. Perhaps he decided that playing competitive chess didn’t really appeal to him: I note that he chose not to take part in club matches in London, when there would have been plenty of opportunity for him to do so.

Lots of questions about his family remain unanswered. It seems probable that his mother was Sarah Ann Hunt, assuming that was her real name. There were several parish baptism records for girls of that name at the right time, but nothing obvious in the 1841 census.

His father may or may not have been Edward Gifford, again if that was his real name. Looking at baptism records and the 1841 census, there’s nothing obvious there. There may well have been some family connection with the unusual Scottish surname Birkmyre, but the exact nature of that connection is uncertain.

If you know more, or if you’d like a copy of my Gifford games and problems database, do get in touch. And don’t forget to join me again very soon for some more Minor Pieces.

Acknowledgements and Sources

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

ChessBase 18/Stockfish 17

chessgames.com: Gifford here

EdoChess: Gifford here

Yet Another Chess Problem DataBase (YACPDB)

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

Google Books:

Jaarboekje van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond Vols 2-4

Sissa (1873)

Old Bailey Online

https://convictrecords.com.au/gerard killoran

Steinitz in London (Tim Harding)

Gerard Killoran

Problem Solutions

Problem 1:

1. Nef2+ Kf5 2. Ke1 Bxg5 3. Qf3+ Bf4 4. Re4 d2#

Problem 2:

1. Qh6 Kxe3 (1… Qxh6 2. Ng4#) (1… Qxe3 2. Nc6#) (1… Nxe2 2. Rd3#) (1… Bxd5 2. Nc6#) (1… Qxg3 2. Nc6#) (1… Qf4 2. Qxf4#) 2. Ng4#

Problem 3:

1. Nb8 {Threat: Rc6#} Kxc5 (1… Ne7 2. Ree5 h3 (2… Nd5 3. Rc6#) 3. Ne4#) (1… Nd4 2. Rxd4+ (2. Re6+ Kxc5 (2… Nxe6 3. Rc6#) 3. Na6#) 2… Kxc5 (2… Rd5 3. Rc6#) 3. Nb3#) 2. Qa1 Kd6 (2… Ne3 3. Qa3#) (2… Kb4 3. Na6#) 3. Qe5#

Leave a comment